Today is Victory in Europe Day, 80-years since the guns fell silent across a continent and the Second World War came to an end in Europe.

Just days beforehand, Hitler had died by suicide as Berlin echoed with the thunder of Soviet troops closing in.

On May 7th, General Alfred Jodl of the German Army signed the act of unconditional surrender at the Allied Expeditionary Force’s headquarters in France, bringing hostilities to an end just after midnight.

“The German war is therefore at an end,” Churchill told the British people in a BBC broadcast, before adding, “We may allow ourselves a brief period of rejoicing.”

After six long years of heartache and heroism, the streets of London echoed with the sound of jubilant cheering.

Winston Churchill waving to crowds in Whitehall, London on Victory in Europe Day 8th May 1945. Picture by: Alamy.com

Winston Churchill waving to crowds in Whitehall, London on Victory in Europe Day 8th May 1945. Picture by: Alamy.comEight decades on, there are few who still remember that moment and fewer still who served in uniform to bring it about.

One of them is John Patrick McCullough, who joined the British Army at the age of 17 and served in the Royal Ulster Rifles.

Now 103-years-old, the Antrim man has recently moved into the Somme Nursing Home in Belfast, which caters to former members of the British Armed Forces and their spouses.

Despite his age, his memories of the conflict are still sharp.

“I was in the Junior Tank Corps - which was for Bren Carriers,” he told Newstalk.

“A Bren Carrier was a machine gun carrier, you had a driver and a non-commissioned officer, he was the gunner.

“They weren’t tanks, they were tanks’ wee brothers.”

A victory that was hard fought and hard won.

A victory that involved every part of society.

80 years on, we salute the extraordinary generation that liberated our continent and ensured that we, the generations that followed, can continue to live in peace.

#VEDay80 pic.twitter.com/qTirlKMGQc— Ministry of Defence 🇬🇧 (@DefenceHQ) May 8, 2025

Reflecting on his experience, he describes it as “interesting” and a time in his life when he met many good comrades.

“You met people you could do without knowing as well,” he said.

“They weren’t all that friendly - especially when you’re a wee bit more intelligent than they were.”

After joining the Army, Mr McCullough was posted to London for training ahead of the invasion of France.

Following D-Day, he and his comrades were dispatched to the continent.

“At the time, I didn’t know where northern France was, being such a green Irishman,” he said.

“But when we went there we were treated very well by the locals.

“Although the senior regiment that was there, they treated us as wee schoolboys - although we were better shots than most of them.

“We had more time to be on the ranges than they did, they were rushed to the front, you see.”

Today marks the 80th anniversary of #VEDay

Read extracts from letters written by the #VE80 generation, sent to their loved ones during the Second World War#Victory80 | #VEDay80 | @I_W_M pic.twitter.com/ttWIvVzeAm

— Department for Culture, Media and Sport (@DCMS) May 8, 2025

After the liberation of France in 1944, British troops pushed east through Germany, with one town and city after another falling to Allied forces.

Mr McCullough was not among them, having been injured in the leg.

“People who were injured were no use to them, so I was sent back to England and the Regiment,” he said.

“A grenade was launched by the enemy and shrapnel whacked my leg and put me down.”

🗣🙌VE Day: 'It is so important to remember. What a generation of heroes.'

🎤🎥Chief Reporter @jamesgould23 speaking to deputy First Minister @little_pengelly.

📍It comes as events are taking place across Northern Ireland and beyond this week to mark the end of the Second… https://t.co/1liPUjJXxP pic.twitter.com/BWkUr5wx45

— Cool FM News (@newsoncool) May 6, 2025

Despite the jubilation after the defeat of Nazi Germany, few troops found life easy when they left the Armed Forces.

Millions of people across Europe had been murdered, much of the continent lay in rubble and returning to civilian life was a difficult adjustment.

In Northern Ireland, Mr McCullough found it hard to find employment.

“There was no work for you,” he recalled.

“They didn’t have work for people shooting guns and quite a number of people from the south of Ireland had come up and taken up the civilian jobs.”

Ireland's Emergency

Naturally, people’s experience of the Second World War was different south of the border.

While Dublin’s North Strand was bombed and many thousands of Irishmen and women had joined the British Armed Forces, Irish neutrality meant the Allied victory had a different meaning.

Richard Behal, who now lives in Dublin’s Maryfield Nursing Home, recalled how the deep resentment many Irish people had towards the British influenced their view of the conflict.

“I can say from my feeling of it generally that there was a lot of sympathy with Germany," he said.

"People didn’t understand what we found out later towards the end of the war, the Belsen camps and the horror of the extermination camps.

“We would have seen the old foes up against it and they were threatening us at times with invasion over the border.”

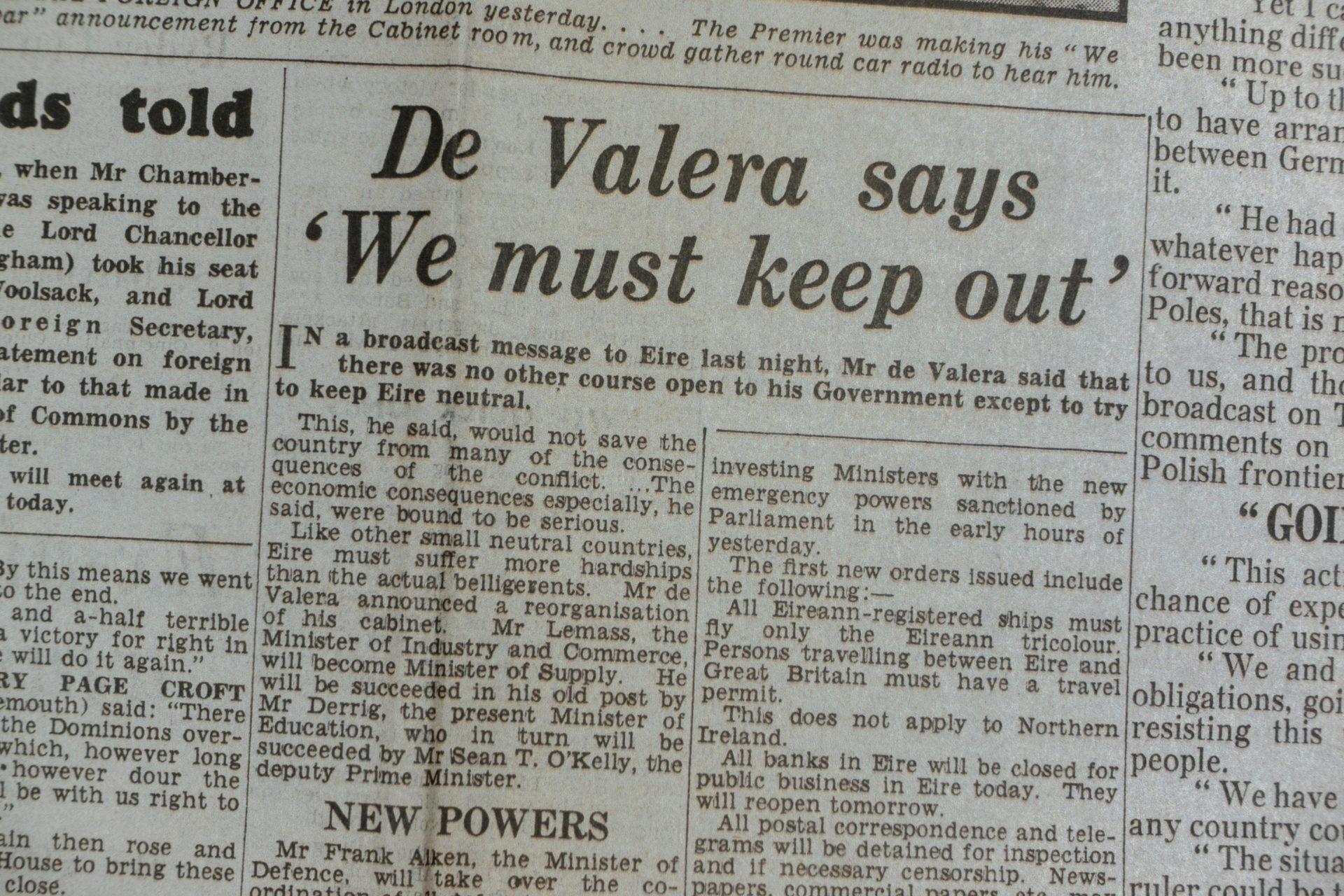

An article about Irish neutrality in The Daily Express from 1939. Picture by: Alamy.com.

An article about Irish neutrality in The Daily Express from 1939. Picture by: Alamy.com.Others at the Maryfield have a different recollection of the period.

Sister Marie-Celine O'Byrne has “very clear memories” of how the conflict changed her childhood in Ardagh in County Donegal.

At the age of seven in 1939, she missed out on a family trip to Derry and her father came home to tell her the war had begun.

“My father would be invariably listening to the radio for war news,” Sister Marie-Celine said.

“As children, we would not be allowed to speak when the radio was on because my Dad was listening to it.

“We knew that Germany was in the war, Germany and Britain - that’s really all we knew at the time.

“And Germany was very bad and Britain was good.

“We knew about this man called Herr Hitler and there were some funny songs about Herr Hitler as well; we knew he was a bad man and we also knew the British had bombings.”

An acrimonious aftermath

Soon after VE Day, Churchill made clear that he had been infuriated by Irish neutrality during a “deadly moment in our life”.

“However with a restraint and poise with which history will find few parallels His Majesty’s Government never laid a violent hand upon them...and we left the de Valera Government to frolic with the Germans and later with the Japanese representatives to their heart’s content,” he raged.

In response, de Valera, who had recently offered his condolences to the German legation after the death of Hitler, suggested that Churchill, “find it in his heart to acknowledge that this small nation had stood alone, not for one year or two, but against aggression for several centuries and not surrendered her soul.”

Main image: WWII veteran John Patrick McCullough. Image: Newstalk