They come in their dozens on All Souls’ Day to gather in the shadow of Edward Carson’s imposing statue on the Stormont Estate.

Mostly elderly men and silver haired ladies, a handful propped up by walking sticks; these are the victims of the Troubles whose grief is still raw and emotional.

Over 3,000 people died across these islands and beyond because of the Troubles. But whether they were saints or devious sinners, almost all were given the dignity of a Christian burial, surrounded by their loved ones in the days after they breathed their last breaths.

But not the loved ones of these pensioners. These are the Families of the Disappeared, the victims of the Troubles who were killed and whose bodies were then hidden away - mostly in boglands; covered hastily by their killers with a shallow layer of earth, all far away from their homes, in places unknown to those who held them dear.

The group begin their annual Silent Walk for the Disappeared up the Stormont Estate towards the Northern Ireland Assembly.

It is their 19th walk and they come in the pouring rain or dazzling sunshine to support each other and catch up. Not even the pandemic in 2020 put a stop to this moment of love and solidarity.

The families march slowly and pause halfway up for a brief appeal to those who may know something, but have yet to come forward. Dympna Kerr speaks first, her voice sometimes breaking with the emotion and the pain of 50 years of endless grief.

Families of the Disappeared outside Stormont. Picture by: Alamy.com.

Families of the Disappeared outside Stormont. Picture by: Alamy.com.“Five of our loved ones have not yet been recovered,” she intones solemnly.

“My younger brother, Columba McVeigh, Joe Lynskey, Seamus Maguire, Robert Nairac and Lisa Dorrian. We hope in silence. The fear is now passed - that’s gone.

“We urge anybody with any information to please pass it on. Please do the right thing for us all.”

Fr Joe Gormley reads the prayer for the Disappeared and there is a chorus of Amen, followed by hands flying up and down in the shape of the Cross. Overwhelmingly, the Disappeared were from the North’s Catholic community.

The group then walks up to the steps of the Stormont Assembly and poses with a wreath, many in sunglasses as they stand facing towards the blazing autumn sun, their minds on the painful events of decades ago.

Photographs are snapped for the local newspapers, then the Families retreat down the steps for more press interviews, after which their sad duty to their loved ones is completed for another day.

Next year on All Souls’ Day, they will return again. And again and again and again, until all the Troubles’ Disappeared are found and buried with the dignity they were denied when they died.

Marie Lynskey holds a photograph of her uncle, Joe Lynskey. Picture by: Alamy.com.

Marie Lynskey holds a photograph of her uncle, Joe Lynskey. Picture by: Alamy.com.It’s often said that funerals are done well in Ireland. RIP.ie is both a national institution and an affectionate joke.

It is the moment for a community to wrap their arms around the bereaved, share cheering stories and offer prayers of comfort.

So what happens when you’ve no body to bury? Is it possible even to mourn? How can you really know your loved one is actually gone?

For the loved ones the Disappeared leave behind, the impact on their mental health is usually profound.

Burial is intrinsic to the human condition. It separates us from our animals neighbours; many species grieve but most leave their loved ones’ bodies where they fall. But the Disappearance of the dead has a long, ugly tradition in war.

Throughout Irish history, there has been no mark of shame greater than being branded an informer. Historian Peter Hart described them as a “symbol of evil since the days of penal law and priest hunters”. It was a stain on a person’s reputation that was whispered on through the generations.

Unlike British soldiers, who mostly had accents and mannerisms from the neighbouring isle, local informers blended seamlessly into the community. It was why they were so feared by republicans and why the punishment for their supreme betrayal was death.

During the 1798 Rebellion, the United Irishmen were responsible for a number of Disappearances. Burying a man secretly meant there was still doubt about the whereabouts of the executed, thus minimising the chance of vicious reprisals by British Crown forces.

It also created a climate of fear and panic among those on the pro-British side.

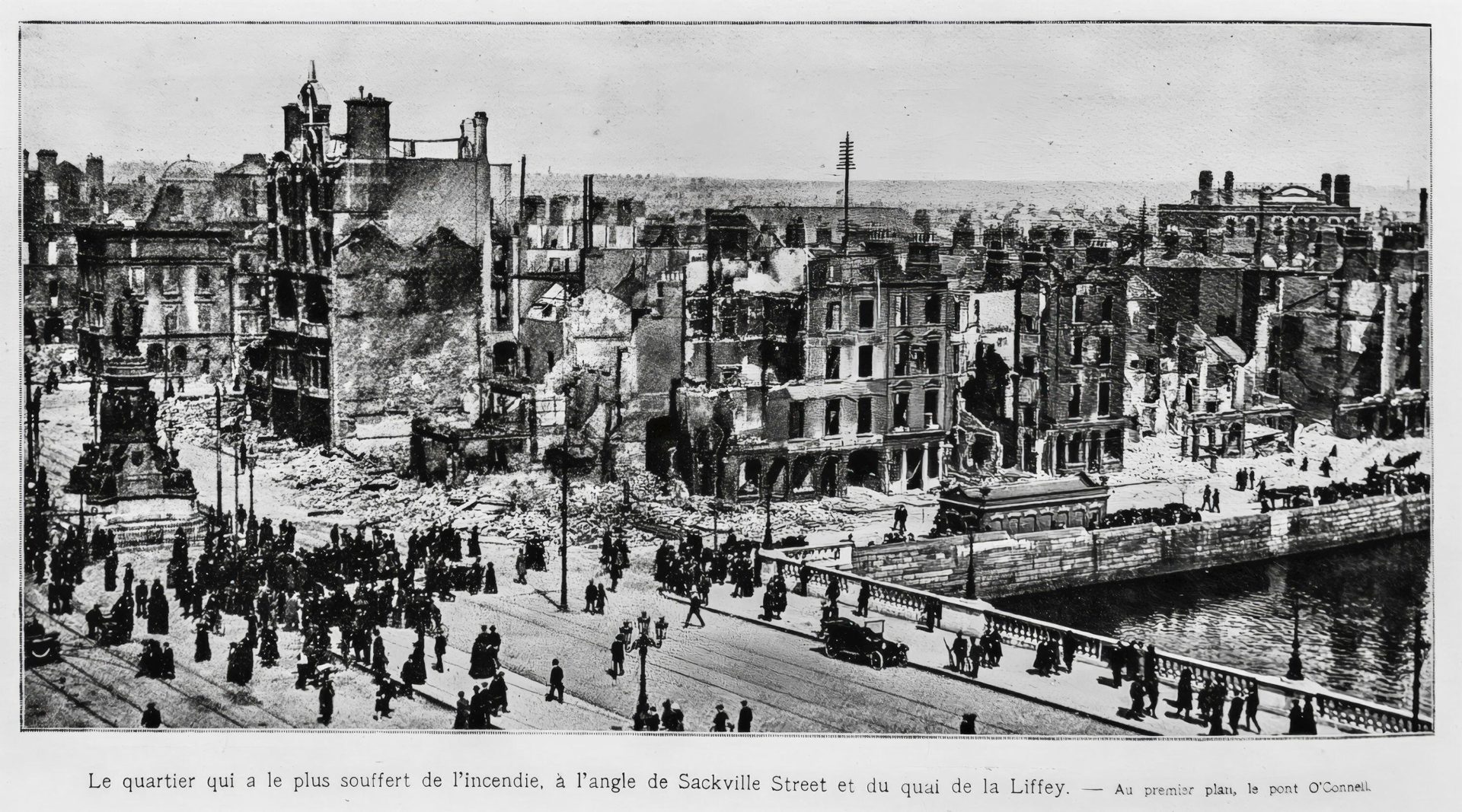

Over a century later, days after the Easter Rising was suppressed, 17 unarmed civilians were murdered in Dublin by the British Army. Six of the victims were secretly buried in an attempt by the South Staffordshire Regiment to conceal their crimes.

It was only two weeks afterwards that the full extent of the massacre was uncovered when a barman at O’Rourke’s Public House complained of a “heavy smell” coming from the cellar. Two men had been buried in the pub, while a further four were later found in a local dairy.

Dublin in the aftermath of the Easter Rising. Picture by: Alamy.com.

Dublin in the aftermath of the Easter Rising. Picture by: Alamy.com.In the War of Independence, dozens, perhaps hundreds, of alleged civilian spies were Disappeared by the IRA. Generally, they were buried in bogs, forests or the mountains.

Occasionally, it was graveyards and in the Midlands, local IRA brigades favoured rivers. Jerome Davin, Commandant of the 1st Battalion, 3rd Tipperary Brigade, disliked the idea of leaving the bodies of the IRA’s enemies dumped on the roadside, as sometimes happened.

“That policy embarrassed the people who lived in the houses near where the bodies lay and perhaps resulted in reprisals being carried out on those people,” he complained.

“I preferred to have the spy buried quietly and leave an air of mystery about his fate.”

'Haunting me all my life'

When the Troubles broke out, the Disappearances began again. At least 17 people were kidnapped, killed and then secretly buried by republicans. While in 2005, Lisa Dorrian, a 25 year old County Down woman, vanished, never to be seen again. It is thought that she was murdered by loyalist paramilitary members.

Other people were most likely Disappeared as well, but their families simply never approached the authorities - such was the stigma and fear of reprisals.

Of all the thousands of victims of the Troubles, Jean McConville is perhaps the most famous. Just a few weeks before Christmas in 1972, the widowed mother of 10 put her coat on and left her home in Belfast’s Divis Flats for the last time.

Around a dozen members of the IRA had burst into the family home, most of them wearing balaclavas or nylon stockings to cover their faces. The youngest of the McConville children screamed as their mother was taken down the stairs of the Divis Flats complex, bundled into a blue Volkswagen van at gunpoint and never seen again.

Helen McConville with a picture of her mother, Jean. Picture by: AP Photo/Peter Morrison.

Helen McConville with a picture of her mother, Jean. Picture by: AP Photo/Peter Morrison.She was, the community was told, that most unforgivable of things - a tout working for the British Army.

A month later, the BBC told viewers that she “had been unceremoniously removed from her home”. The IRA claimed she was simply “lying low” but in fact, they had fired a bullet into her head and dumped her body some 50 miles away in County Louth.

Soon afterwards, Ms McConville’s orphaned children were taken into care after two of her sons were caught shoplifting chocolate biscuits. He and his siblings were starving, he explained to the police.

Billy, Thomas, Michael, Arthur and Robert McConville. Picture by: Joe Dunne/Photocall Ireland.

Billy, Thomas, Michael, Arthur and Robert McConville. Picture by: Joe Dunne/Photocall Ireland.For decades, the IRA denied killing Ms McConville and her body was only found in 2003 after a dog walker stumbled upon her remains. A police ombudsman report later concluded there was no evidence that she had ever been a British Army informer.

Millions of people now know the intimate details of her life and tragic death thanks to the best selling book Say Nothing by Patrick Keefe, which was later made into a nine part Disney series.

For those who watched it, it was no doubt an enjoyable way to spend a few hours, dipping in and out of the horrors of the Troubles, all from the comfort of their own home. But for the McConville children, it was deeply upsetting to see their family’s enduring trauma rebranded as entertainment.

Speaking to Newstalk Breakfast when the series was released in 2024, Michael McConville described his mother’s death as something that “has been haunting me all my life”.

“I thought when we found my mother’s body that was the end of the nightmare - that was only the beginning of it,” he added.

“After one thing after another, with people doing things about our mother, it keeps reappearing all the time.

“Hopefully this is the last thing that’s going to happen because I don’t know which way my family is going to go after this.”

Michael McConville, son of Jean McConville, at his parents' grave in Lisburn. Picture by: Alamy.com.

Michael McConville, son of Jean McConville, at his parents' grave in Lisburn. Picture by: Alamy.com.It is a suffering that Linda Pywell understands well. Her brother, Brian McKinney, was kidnapped one morning in May 1978 and never seen again.

It is, she said, something that has impacted her family’s mental health “enormously” over the years.

The family lived in the republican heartland of West Belfast and a few days beforehand, Mr McKinney had been ‘arrested’ by the IRA at the time in connection to a local robbery.

Only 22 at the time, were he alive today it is likely he would be diagnosed as having special needs.

This detail is perhaps not incidental to the story of his life; Dr Jack Nabney, who worked as a psychiatrist in Northern Ireland, felt people with mental illness - and presumably also those with special needs - were at greater risk during the Troubles because they often lacked awareness of the danger that lurked around them.

After their son failed to return home after work, the McKinneys’ fears were confirmed when a colleague arrived with his wages in a brown envelope. He hadn’t turned up for his shift and the family instantly suspected the IRA.

“We just didn’t know what to do or where to go,” Ms Pywell recalled.

“As the weeks went on, they became months and the months became years, it was awful.

“Because you know in your head that he must be dead, he has to be dead because nobody could keep him from us.

“If there had been a way to get in touch with us, he would have found it because we were a very close family.

“So, you knew logically he must be dead but because you didn’t ever get his body and you didn’t bury him, somehow you still hang onto that thread of hope.”

Linda Pywell and Margaret McKinney at the funeral of Brian. Picture by: Alamy.com.

Linda Pywell and Margaret McKinney at the funeral of Brian. Picture by: Alamy.com.In the years afterwards, the McKinneys lived in a daze. One brother had a severe mental breakdown and received no treatment, while the two sisters left Belfast to get away from the unhappy atmosphere at home.

The stress of not knowing what had happened was compounded by their community’s indifference and even outright hostility towards them.

“For 17 years, nobody came near us,” Ms Pywell added.

“We had no help from any authorities or church groups or even neighbours.

“In those days, if someone went missing, it was just assumed that they had committed some sort of an offence against the IRA and they were the police at the time.

“It was usually suspected that they would have been an informer or something like that; so, there was a general feeling in the community [that was] not one of sympathy.”

The funeral of Brian McKinnney. Picture by: Alamy.com.

The funeral of Brian McKinnney. Picture by: Alamy.com.Eventually, the family gave up all hope that he would return and many years later the focus shifted to finding his body. Margaret McKinney, Brian’s mother, became involved with the WAVE Trauma Centre and realised that it wasn’t just her son who had been Disappeared.

To this day, the Families of the Disappeared speak of Ms McKinney with huge affection, describing her as a force of nature, who sang songs at their meetings and kept their spirits up.

The turning point came shortly after the Good Friday Agreement, when she met Bill Clinton at the White House. The President of the United States listened, visibly moved, to the Belfast housewife who just wanted to bury her son.

Clinton told her he would do everything he could to help and some weeks later a senior republican knocked on their front door. Two decades after Mr McKinney’s murder, the IRA promised to reveal the location of his burial - and those of the other Disappeared.

But it wasn’t as simple as just telling the authorities where the bodies were buried.

“A lot of these murders took place 30, 40 years ago in some cases,” Ms Pywell explained.

“The perpetrators, some of them weren’t alive or were much, much older and maybe couldn’t remember.

“And also, the locations where they’d hidden the bodies - which were all over the place, North and South of the border - the terrain and the foliage and all of these things had changed in the years.

“So, even those people went back to try and remember where they’d hidden the body, they sometimes couldn’t locate it because it looked different.”

The funeral of Brian McKinney. Picture by: Alamy.com.

The funeral of Brian McKinney. Picture by: Alamy.com.In the summer of 1999, diggers were brought up to a bog in Colagh, County Monaghan, just a few miles from the border. For 30 days, they carefully excavated the bogland until, at last, human remains were found.

Mr McKinney and his friend, John McClory, who was Disappeared at the same time as him, had been buried together in a double grave.

“For us, it was a huge sense of relief and we were very grateful to receive his remains back again,” Ms Pywell recalled.

“We were able to give him a proper funeral and bury him in Milltown Cemetery, where the grave was visited every day.

“That gave my parents so much comfort that they were able to go and visit his grave every day… at least once.

“Now, Mummy and Daddy are both in the grave with Brian and my sister, she lives nearby, and she goes regularly.

“When I come over from England, I always go there too - and we still find peace when we go there and a closeness.”

The search continues

In the autumn of 2025, former Garda officer Eamonn Henry pulled on a pair of wellington boots and a fluorescent jacket. A few months previously, he had been appointed the lead investigator for the Independent Commission for the Location of Victims' Remains.

The autumn sun blazed downwards on Bragan Bog in County Monaghan, while the wind whipped strongly through the open bogland.

“This place has its own ecoclimate,” he said, as the door clanged shut on the portacabin behind him.

“This place is owned by Coillte, the forestry managers for Ireland.

“You see the wind farm over there? That’s due north, that’s Northern Ireland over there. [We’re] no more than two miles from the border I’d say.”

Bragan Bog in County Monaghan. Picture by: Alamy.com.

Bragan Bog in County Monaghan. Picture by: Alamy.com.On Bragan Bog, there’s not a house as far as the eye can see and it is thought that somewhere in this vague area lie the remains of missing teenager Columba McVeigh.

A Catholic, he grew up in Donaghmore, County Tyrone, where he was an outgoing character who played Gaelic football and liked acting and dancing.

After rumours spread through the village that he was working as an informer for the British Army, he left Tyrone and moved to Dublin. On Halloween night 1975, he told a housemate he was going for cigarettes and was never seen again.

Although his family hoped he had fled to England or America, he had in fact been abducted and murdered by the IRA.

Looking for Mr McVeigh has never been a simple task. There have been multiple searches for him since the Good Friday Agreement but the exact location of his body has always eluded those looking for him.

“You can see the conditions which we have to work in,” Mr Henry explained as diggers carefully prized open the brown earth around them.

“If it rains, it really makes it quite difficult to manage and to conduct the searching because you see the steel mats? Sometimes the diggers can slide off those, if it’s excessive rain.

“So, we have to manage the water and keep it away as much as possible from the area we’re operating in.”

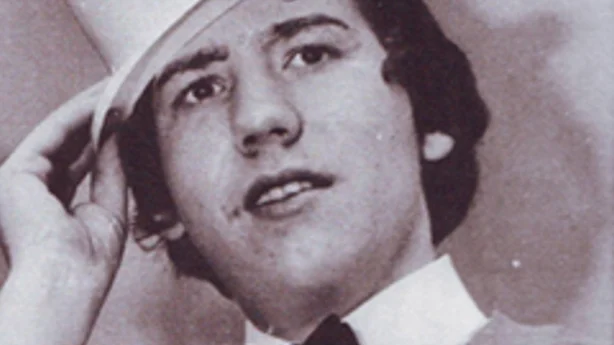

Columba McVeigh. Image: Supplied.

Columba McVeigh. Image: Supplied.Despite this, Mr Henry has always been optimistic that one day, Mr McVeigh will be found and buried in his family plot with the dignity he was denied five decades ago when the IRA took his life.

“We believe we’re in the right area,” he said.

“But we just haven’t hit the right spot, as such, as to where he’s been buried.

“We’ll continue to search all the ground that we have identified that needs to be searched until, hopefully we do find him.

“I’m confident that eventually we will find him and, by all accounts, we are in the right area. So, God willing, we will find him.”

It was, it turned out, a forlorn hope.

Just before Christmas, an email pinged into the inboxes of journalists’ inboxes across Ireland. The seventh search for Mr McVeigh had come to an unsuccessful end.

Dympna Kerr on Bragan Bog. Picture by: Alamy.com.

Dympna Kerr on Bragan Bog. Picture by: Alamy.com.For Dympna Kerr, Mr McVeigh’s older sister, it was devastating news.

Now living in the North West of England, his Disappearance plunged her family into a “limbo” that still ensnares it.

“We didn’t know whether he was living or dead,” she recalled, Mr McVeigh’s photo looking down on her from the mantlepiece.

“My mother talked about him [as if he were] alive, I always said he was dead.

“We used to have conversations here on the phone and she’d tell me off as soon as I said, ‘Columba’s dead.’ She would get really cross with me.

“She would say, ‘Pray for him at Mass.’ ‘I do, I always put him in with the prayers for the dead.’ ‘Well, I don’t know why you do that because I put him in the prayers for the living.’

“That’s how it was.”

Simon Harris talks with members of the Independent Commission for the Location of Victims' Remains (ICLVR), during a visit to Bragan Bog. Picture by: Alamy.com.

Simon Harris talks with members of the Independent Commission for the Location of Victims' Remains (ICLVR), during a visit to Bragan Bog. Picture by: Alamy.com.For decades, Mr McVeigh’s parents tried never to leave the house together. Someone always had to be home in case their son came back, who, naturally, after so many years away, would have lost his key.

Ms McVeigh dreamed he would return to Tyrone with a wife and grandchildren for her to spoil.

But after the Good Friday Agreement, a member of the IRA arrived at the home of Mr McVeigh’s brother and read a statement revealing the truth; he had been executed.

Confirmation of his death meant the focus shifted onto finding his body and bringing it home for burial.

Both Mr McVeigh’s parents have passed away and their headstone has been engraved with his name, anticipating that one day he will join them.

Asked how she would feel at his funeral, Ms Kerr replied that was an “easy one to answer”.

“Happiest woman alive,” she said.

“Don’t get me wrong, I know I will have a tear in my eye.

“I’ve never won the lottery, but I could just imagine that I would be as happy as if I had won the lottery. I mean it from the bottom of my heart.

“Just to get him back; walking behind that coffin into Donaghmore Chapel, to walk back out behind it again, carry it up to the grave, see it lowered in beside my Mum and Dad. It’s all we want… It’ll be the end of a nightmare.”

A wreath and photographs of Columba McVeigh, Joe Lynskey and Robert Nairac outside Stormont. Picture by: Alamy.com.

A wreath and photographs of Columba McVeigh, Joe Lynskey and Robert Nairac outside Stormont. Picture by: Alamy.com.Few people know the Families of the Disappeared as well as Dr Sandra Peake does. The CEO of the Wave Trauma Centre in Belfast trained as a nurse in the 1990s and first met them through her voluntary work with the organisation.

Then, Northern Ireland was a very different place and gaining their trust was hard.

“The reputations of that family member were impugned, so that nobody would make any effort to look for them,” she explained.

“And when the Families started to speak out they were threatened.

“So, if you think about the long-term impact of that, when you have been silenced in that way.”

It was, she added, a “very callous and a very cruel strategy” that punished those who were left behind. Instead of sympathy, they were sneered at in shops and on the street.

Even Mass wasn’t a safe place from angry expressions of moral disapproval.

“The difficulty is for many Families, they never got to grieve, they lived in a community of silence, they were ostracised within that community,” Dr Peake recalled.

“They internalised what happened, they didn’t know who to trust, they couldn’t even go to their GP to tell them what happened.

“Because sometimes their GPs, their cousin could be linked into somebody in the community.

“I think that what’s not understood often about Northern Ireland and the Troubles - but particularly around the Disappeared - this was an intracommunity conflict.

“So, the people who were responsible for your loved ones’ death were living among you.”

The funeral of Jean McConville. Picture by: Alamy.com.

The funeral of Jean McConville. Picture by: Alamy.com.In the aftermath of the Good Friday Agreement, a study found that people in Northern Ireland took 75% more tranquillizers and sedatives and 37% more antidepressants than people in other parts of the United Kingdom.

The years of peace have not healed all wounds and Dr Peake argues many survivors live with “continuous trauma”.

“Today, we’ve a better understanding of that internalisation,” she said.

“That the body holds the score; whilst people may not have voiced it, it came out in different ways.

“We do a lot of work with Queen’s University’s School of Medicine each year where we map our indicators of health.

“We can see that coronary heart disease is 10 years earlier in victims and survivors of the conflict.

“We can see the long-term impact of anti-depressants on gut health.

“We can see the prevalence when you talk to the Families of cancer and other auto-immune disorders. So, there’s no doubt that the Families have struggled.”

The funeral of Jean McConville. Picture by: Alamy.com.

The funeral of Jean McConville. Picture by: Alamy.com.Every time there is a search for her brother, Dympna Kerr comes over to Northern Ireland and the pair head out to Monaghan together to bring tea and biscuits to the workers.

It is a process that is always heavy with emotion.

“I’ve been with the Families when the news has come through that their loved one has been found, I’ve gone down the sites with them,” Dr Peake said.

“There’s that sort of sense of relief that it’s finally over.

“Dympna in the past has spoken in the past about how when the search is ongoing, she feels as if she’s waiting for him to die.

“That may seem very strange because you think, ‘These people are dead three, four decades’ - but that is a common emotion.

“For Families, when they’re found, it’s just as if it happened yesterday. They’re plunged into that grief.”

Dympna Kerr and Sandra Peake on Bragan Bog. Picture by: Alamy.com.

Dympna Kerr and Sandra Peake on Bragan Bog. Picture by: Alamy.com.Finally laying their relative to rest after so many decades of pain is a “cathartic process”, Dr Peake added.

For some, it is the first time they feel the community has acknowledged their suffering.

“There’s also a sense that respect is restored to the family,” she recalled.

“For so long, they’ve been telling the community, ‘My loved one is dead, I believe my loved one is dead.’ And, of course, the denial comes back, ‘No, they’re not.’

“So, for the first time, for many Families, they feel as if they are believed and they feel as if what happened to their loved one has finally been recognised.

“I have long-term seen the benefits for Families of that sort of sense that they’ve been able to give them the rites and rituals of Christian burial.

“It’s laid something to peace within that Family as well.”

The funeral of Brendan Megraw in 2014. Picture by: Alamy.com.

The funeral of Brendan Megraw in 2014. Picture by: Alamy.com.In April 1999, the Irish and British Governments set up the Independent Commission for the Location of Victims’ Remains.

All information passed onto them about the victims is legally privileged and cannot be passed onto other Government agencies or used in a court of law.

So far, the ICLVR has recovered the bodies of 13 of the 17 Disappeared victims of the Troubles.

For anyone with any information about the deaths of Joe Lynskey, Columba McVeigh, Robert Nairac or Seamus Maguire, Dr Peake has a simple message.

“We need to be able to release Families from this,” she said.

“One of the Families said a very powerful thing, ‘When my brother was killed, the pain ended for him but it only started for us.’

“It’s the Families who bear that legacy. They’re not bearing it for one or two years, they’re bearing it for 40, 50 years.

“There’s a cruelty in continuing to conceal information.

“What I would urge anyone to do is end that cruelty, provide whatever you can and allow Families to be able to lay their loved ones to rest.”

The Independent Commission for the Location of Victims’ Remains can be contacted on 00353 1 602 8655 or reached by email on secretary@iclvr.ie.

If you have information about Lisa Dorrian, who Disappeared in 2005, you can contact Crimstoppers anonymously on 0044800 555 111.

If you need emotional support, you can contact Samaritans on 116 123.

This report was supported by the Rosalynn Carter Fellowship for Mental Health Journalism in the Republic of Ireland, in partnership with Shine.

Main image: Relatives of the Disappeared march on Stormont. Picture by: Alamy.com.