The bus from Dublin to Derry passes many flags as it winds its way north, but one in particular catches the eye - the maroon and white banner of the British Army’s Parachute Regiment.

Attached to a lamppost just outside the city, it flutters in the wind as an obvious provocation to Derry’s nationalist community, who lost 14 souls when the Paras opened fire on an unarmed civil rights march on 30th January 1972.

Bloody Sunday, as the day quickly became known, was a day that slashed open a wound from which Derry has never healed. Over half a century has passed and the day still provokes great emotion among those who were there and, indeed, among many who weren’t, but whose lives were changed utterly by it.

Every year on the Sunday closest to 30th January, hundreds of Derrymen and women gather by the memorial to the dead on Rossville Street in the Bogside, just a few steps from the famous ‘Free Derry’ corner. Old acquaintances catch up, remark upon the weather and exchange pleasantries about their pets.

In 1972, Rossville Street was filled with the sound of similar chitchat and jovial exchanges of views. Some 15,000 Derry people had gathered to march and call for an end to the internment without trial of young Catholic men. Protests had won civil rights for African Americans in the United States, surely that could happen in Ireland too?

The Government of Northern Ireland had banned the march and the Army was deployed to police it. Still, there was a carnival atmosphere on the streets of Derry that day. That all changed at 3.55pm when the shooting started. Soldiers of the Parachute Regiment opened fire on the crowd, killing 13 and seriously injuring at least 15 more. One of the wounded, John Johnston, would die some months later, swelling the total death toll to 14.

It is these men and women the crowd have come to remember. The tannoy system bursts into life; prayers are recited en masse and sermons are delivered by local clergymen. Ami Nash, the niece of murdered teenager William Nash, reads out the list of the murdered and wounded, while a tin whistle plays a lament. Floral wreaths are laid by the bereaved and a minute’s silence is held as the people of Derry reflect on the darkest episode in the city’s history and perhaps the most notorious of the Troubles.

John Hume said Bloody Sunday left Derry “numb with shock, horror, revulsion and bitterness”. 54 years have now passed since Hume, who would later win the Nobel Peace Prize, uttered those words in the immediate aftermath of the massacre, but for the families of those murdered, they could just as well be written out today.

The Parachute Regiment had a different version of events. As Derry counted her dead and nursed her wounded, Major General Robert Ford told a journalist that the IRA had fired “between 10 and 20” rounds on his soldiers, forcing them to return fire.

“The Paratroopers did not go in there shooting,” he told the BBC’s millions of viewers.

“In fact, they did not fire until they were fired upon.”

A mural of the 14 peoplekilled by the British Army on Bloody Sunday. Picture by: Irish Eye/Alamy Live News.

A mural of the 14 peoplekilled by the British Army on Bloody Sunday. Picture by: Irish Eye/Alamy Live News.It was a powerful and hurtful lie that caused the bereaved enormous heartache.

British Home Secretary, Reginald Maudling, commissioned the Lord Chief Justice, Lord Widgery, to investigate Bloody Sunday. Widely and bitterly regarded as an establishment whitewash in Derry, his report concluded there "no reason to suppose" the Army had not been fired upon first.

It also pointed the finger at the marchers, who it accused of creating a “highly dangerous situation in which a clash between demonstrators and the security forces was almost inevitable”. It would take nearly four decades for the truth to emerge.

'Just blackness'

In January 1972, Karen Doherty was a mature 11 year old, who used to spend a lot of time with her father. Patrick ‘Paddy’ Doherty was, she recalls, a wonderful man in every way.

“We did everything together,” she says, her face lighting up.

“We went out on walks at night when the rest of them were put to bed. He wouldn't have talked to you much going for the walks, but he was a fantastic father.

“I always think if he hadn't been as fantastic as he was, it would have been easier.”

Karen's brother, Tony, holding a picture of their father, Patrick Doherty. Picture by: Alamy.com.

Karen's brother, Tony, holding a picture of their father, Patrick Doherty. Picture by: Alamy.com.In the run up to Bloody Sunday, the pair had fallen out. Young Karen was eager to join her parents and friends on the march, while Paddy was insistent that she stay home and look after her younger siblings. He suggested she watch a film on the television instead.

The arrival of a large crowd of people at the Doherty home was the first indication that something had happened, although at first Karen assumed her fun-loving parents were hosting a party. It was only when she realised the adults were ignoring her that a faint sense of worry crept over her.

“There was this wee boy in the street and he says, ‘Karen, your Daddy was shot over the Bogside’,” she recalls.

“And I ran upstairs and I cried and I prayed so, so hard; I prayed and prayed and prayed to God, ‘Let him live, let him live.’

“I can't remember coming down, but when I did, the house was packed.

“And I was sitting in the chair and I remember my Mammy coming in and my Grandad was with her; all I could see was she was sheet white and one tear.

“She told me and I just lost it.”

St Mary's Church on the Creggan Estate in the aftermath of Bloody Sunday. Picture by: Alamy.com.

St Mary's Church on the Creggan Estate in the aftermath of Bloody Sunday. Picture by: Alamy.com.The death of Paddy changed the Doherty family forever - talking about her father still makes Karen’s voice break with emotion. However, his absence was rarely mentioned, even if it was always felt.

“We didn't talk about it, we didn't mention my Daddy to each other,” Karen explains.

“I think we were all grieving in our own way.

“I remember about three weeks [after], I went down to the bathroom and I was looking at myself, looking at my hair, looking at my skin and I hadn't washed my hair, my skin was all dry.

“I was only 11 but I remember thinking, ‘What is wrong with me?’ When I looked back, I was depressed.

“But I didn't know, I didn't know what was wrong. It was just black, it was just blackness.”

The graves of Bloody Sunday victims. Picture by: Alamy.com.

The graves of Bloody Sunday victims. Picture by: Alamy.com.A study carried out by Ulster University in 2003 found that the children of those murdered on Bloody Sunday still suffered ‘significant psychological distress’, even three decades on from their parents’ deaths.

For immediate family members of those killed, the research found the impact of Bloody Sunday on their mental wellbeing was comparable to veterans of the Vietnam War who experienced combat and members of the South African police who had been recently exposed to violence.

In recent years, Karen has been prescribed antidepressants.

“I wasn't always on them, but I always suffered from anxiety, really bad anxiety, all my life,” she explains.

“I think that because I lost my Daddy and because of the changes in our home, I had no confidence, I had no self-esteem.

“I just was very quiet and withdrawn; I'm a lot better now because I started hairdressing and you have to talk when you’re a hairdresser.

“My boss used to take me in and say, ‘Karen, you're a great wee hairdresser, but you need to talk.’

“I think it was that I didn't want people to know who I was; as a teenager, you don't want any attention.”

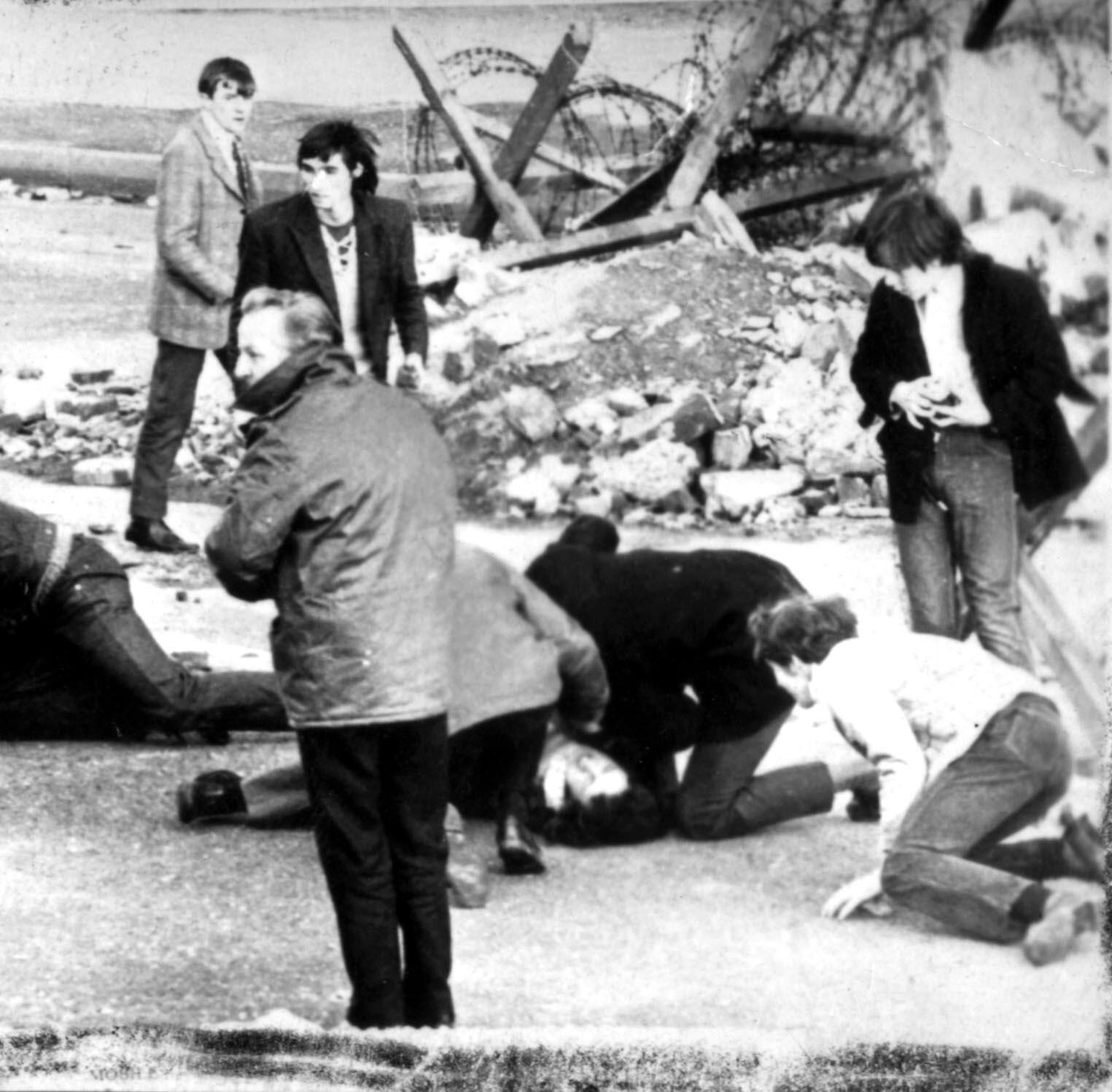

A photo from Bloody Sunday, which shows youth in a sports jacket (extreme left, at top) that is thought to be Michael McDaid, 17, who was killed later that day. Picture by: Alamy.com.

A photo from Bloody Sunday, which shows youth in a sports jacket (extreme left, at top) that is thought to be Michael McDaid, 17, who was killed later that day. Picture by: Alamy.com.Kevin McDaid remembers his older brother, Michael, as a “typical Derry lad”. He was the second youngest of 12 children and only 20 years old when he was gunned down on Bloody Sunday.

A hard worker, who kept himself “neat and clean”, he even had his own car - no mean feat in a poverty stricken place like Derry in the 1960s.

Kevin remembers the morning of Bloody Sunday as cold and crisp, with the skies above the marchers bright blue.

“The lead up was just everybody sort of excited, looking forward to the march,” he recalls.

“No real bother, everybody was enjoying the craic. It was just such a good atmosphere.”

When the Army first opened fire, Kevin remembers everyone running for cover.

“You could hear the shooting and to me, it was constant,” he adds.

“I ran over Chamberlain Street, I got into the car park on the flats and there was a sergeant on my right-hand side.

“And I hear the shot look around at the soldier and he had fired the shot.

“Just in front of me was Jackie Duddy sprawled out. After that, I just ran ahead, scrambled, crawled.”

The monument in memory of the Bloody Sunday in Derry. Picture by: Alamy.com.

The monument in memory of the Bloody Sunday in Derry. Picture by: Alamy.com.Kevin weaved his way through the terrified crowds and made his way home. There he found his family in a state of panic, asking him if he had seen Michael?

John Hume had heard that he had been arrested, but later that evening two ashen-faced priests knocked on their front door. Michael had not been arrested, they said, he had been killed.

When asked about how his brother’s murder affected his mental health, Kevin replies with a quiver in his voice that the legacy of Bloody Sunday has not been “easy” to cope with.

“It's something that, as family members, we have to do to keep it alive,” he explains.

“We're making sure that this is never forgotten.

“If you look at Paratroopers, months previous, they massacred Ballymurphy and then came here. They were soldiers; it proves they wanted to get away with it.

“We have to do what we're doing, as family members, community members, to keep their names alive and love for justice. Which will never end until we get justice.”

The truth emerges

The lack of any criminal repercussions is an issue that is still a cause of intense upset for the families of those murdered.

In 2010, the Saville Inquiry tossed out the conclusions of the hated Widgery Report and exonerated the dead of Bloody Sunday.

Set up in 1998, it was the longest inquiry in British history and, at a cost to the public purse of £200 million, the most expensive as well.

Following its publication, Britain’s then Prime Minister David Cameron told the House of Commons that the actions of the Parachute Regiment were “unjustified and unjustifiable”.

Beamed live to a crowd outside the Guildhall in Derry, his words were echoed by thousands roaring their approval.

People in Derry watch David Cameron make a statement in the wake of the Saville Inquiry. Picture by: Alamy.com.

People in Derry watch David Cameron make a statement in the wake of the Saville Inquiry. Picture by: Alamy.com.For the families, the Saville report was a huge relief. The truth was finally on record and their loved ones were declared innocent to the world. But more than a decade and a half has since elapsed and not a single soldier has served a day in prison.

In 2025, a former member of the Parachute Regiment was put on trial, accused of murdering James Wray and William McKinney, as well as five counts of attempted murder.

Soldier F, as he was called in court, was found not guilty of all charges, after the judge concluded there was insufficient evidence to convict him.

For Joe McKinney, brother of William McKinney, a conviction would have made a “massive difference”, but he always expected an acquittal.

“Every single Paratrooper that gave evidence [in the aftermath of Bloody Sunday] was telling lies,” Joe says.

“So, how can we use their evidence to prosecute them? So, who told them to tell the lies? The Ministry of Defence solicitors that interviewed them.

“So, it was always going to be an uphill struggle for the trial judge to convict them, given the lies they told.”

Relatives of Bloody Sunday victims arrive at Belfast Crown court for the trial of Soldier F. Picture by: AP Photo/Peter Morrison.

Relatives of Bloody Sunday victims arrive at Belfast Crown court for the trial of Soldier F. Picture by: AP Photo/Peter Morrison.Joe adds that while he does not believe in the death penalty, he views Soldier F as an especially mendacious individual.

“Soldier F stood out,” he says bluntly.

Still, despite the decades of struggle foisted on him, he remains unsure about what toll it has taken on his mental health.

“I think I was able to compartmentalise what happened and put it away somewhere until something else brought it out,” he explains.

“When I got married and we had children, they knew about Willie, but I wouldn't have tried to make them bitter - not even against the Army or to blame either the English people or British people.

“So, it's a hard question to answer. I'm sure that it has affected me, but how, I have no idea.”

A supporter of Soldier F protests outside the Palace of Westminster in London. Picture by: Alamy.com.

A supporter of Soldier F protests outside the Palace of Westminster in London. Picture by: Alamy.com.Karen has a clearer idea of how the trial of Soldier F impacted her. For years, her father’s belt with a bullet hole in it had been stashed away in her grandmother’s attic in anticipation of a trial.

It was a forlorn hope. While the Saville Inquiry concluded there was “no doubt” Soldier F had shot Paddy Doherty, the Public Prosecution Service for Northern Ireland decided not to charge him in connection to his death.

Granted anonymity by the court, Soldier F gave his evidence obscured behind a blue curtain and Karen never set eyes on the man who changed her life forever.

“I remember thinking to myself, ‘He’s in there and look what he’s done to our family,’” she recalls.

“I just felt this rush of pain, anxiety and anger; I'm not an angry person, but I felt overwhelmed and I had to get up.”

Former Paras protest in London in support of Soldier F. Picture by: Alamy.com.

Former Paras protest in London in support of Soldier F. Picture by: Alamy.com.Also in attendance was Ami Nash, whose uncle, William Nash, Soldier F was accused of murdering. Her grandfather, Alexander Nash, was wounded as he went to try and save his dying son.

Years elapsed between the murder of her uncle and her birth, but Bloody Sunday is a day that is deeply embedded within Ami’s psyche. Despite this, as a second generation Bloody Sunday family member, she suffers at times from imposter syndrome.

“When I was at the Soldier F trial, I [wondered], ‘Do I belong? Should I be here?’” she explains.

“We were about to go into the courtroom and then the security man said, ‘William Nash.’

“I looked around and I sort of stepped forward, ‘I'm here to represent my uncle.’

“There's some times in your life that you'll never forget and I will never forget that moment, because I just felt a deep sense of belonging.”

Kate Nash with a picture of her brother William. Picture by: AP Photo/Peter Morrison.

Kate Nash with a picture of her brother William. Picture by: AP Photo/Peter Morrison.At weekends, Ami works part-time at the Museum of Free Derry, relating her family’s great tragedy and the city’s story to visitors from around the world.

It gives her plenty of opportunities to reflect on how different her own life would have been were it not for the events of 30th January 1972.

“I help out in my other uncle's house [and] I always sit and wonder what could have been with my uncle Willie,” she says.

“Willie loved country music; he seemed like he was just an amazing person and I feel like we're robbed of that experience.

“I wonder what Willie's life could have been like - getting married and having children, maybe he would have left Derry? Maybe he would have done music?

“But we'll never know what his life could have been because it was taken from him.”

The Nash family. Picture by: Alamy.com.

The Nash family. Picture by: Alamy.com.Each year at the Bloody Sunday memorial event, the names of relatives who have passed away over the previous 12 months are solemnly read out.

At some point in the coming decades, no one alive will remember Bloody Sunday but Ami is determined that their stories will live on.

“These people are my heroes,” she says clearly.

“Not only did they live through such a trauma, but they've done so much for the Bloody Sunday justice campaign.

“The things that they've achieved should never be forgotten.”

If you need emotional support, you can contact Samaritans on 116 123.

This report was supported by the Rosalynn Carter Fellowship for Mental Health Journalism in the Republic of Ireland, in partnership with Shine.

Main image: Commemoration of Bloody Sunday in Derry. Picture by: Newstalk.