On Somerton Road in North Belfast, an array of fairy lights and well-decorated trees tell you it’s Christmas time.

But for a couple of dozen party goers, all dressed up smartly, Christmas is not a holiday that they celebrate; they are the Jews of Belfast and they are arriving at their local synagogue for a Hanukkah party.

In the story of Ireland, religion has often seemed like a binary choice: you are either a Catholic or a Protestant. In fact, there have been Jews in Ireland since at least the 14th century and the first synagogue was established in Dublin in 1660.

Ireland’s Jews have always been small in number and concentrated in the larger cities. Most live in Dublin and in 2016 the only synagogue in Cork shut its doors for good.

It is a fate that the Belfast Synagogue has so far managed to avoid, but a quick glance across the room suggests it is only a matter of time.

Overwhelmingly, they are pensioners - the men’s grey hair only partially obscured by their kippahs - and there is just one family with young children in attendance.

Hanukkah is the Jewish the Festival of Lights. In 175 BC, King Antiochus banned Judaism and ransacked the Temple of Jerusalem. When the Jews returned they found a single jar of oil - enough to light the Temple’s candles for one day. Miraculously, the light kept burning for eight days and ever since Jews have lit candles in their own homes to celebrate.

Even in the darkest of times, Hanukkah has been celebrated.

It was marked secretly in concentration camps and took place over Zoom during the pandemic. This year, there is a far more joyful atmosphere. Colourful balloons spell out ‘Happy Hanukkah’, a kosher feast awaits the faithful and Jewish fiddle music fills the air.

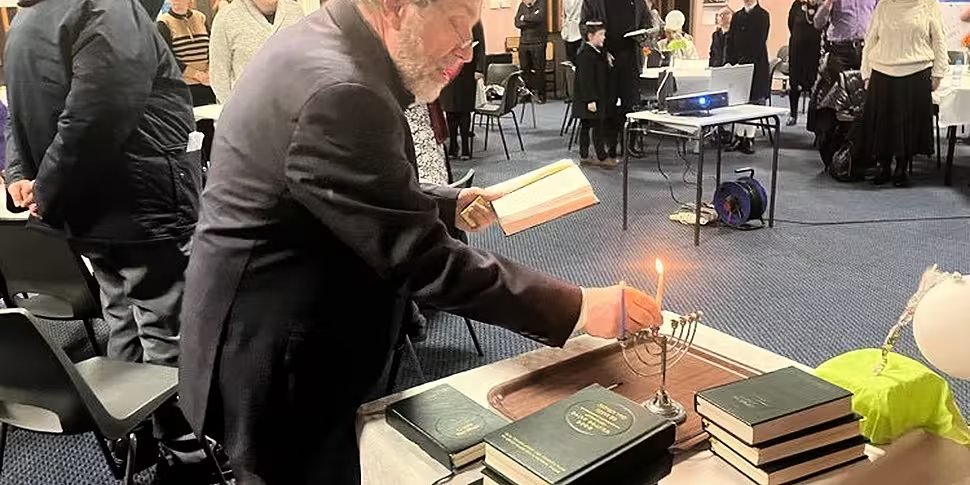

Presiding over the ceremony is Rabbi David Kale, who has carefully placed a menorah next to a copy of the Torah.

“We’re going to make three berakahs, blessings tonight,” he tells his congregation, having lit the first candle.

“One of which is to thank God for allowing us to be alive for another year to be able to celebrate this wonderful festival.

“The other one is a blessing to say we’re actually lighting the candles, and the other is to tell us that God performed miracles for us."

A former solicitor, Rabbi Kale spent eight years learning his craft and moved from London to Belfast in 2018.

It is, he feels, a special privilege to serve in such an unusually intimate community.

“Everybody knows everybody else,” he says.

“If one person is missing from a synagogue service, everybody asks why and everybody notices straight away.

“Here in Belfast, the community is small but everybody is very warm, everybody is very friendly - as is the non-Jewish world.

“They show a great deal of respect to the Jews of Belfast.”

It is that sense of community that many of the attendees value the most. The word ‘family’ comes up more than once when Belfast Jews describe how they feel about their coreligionists.

For Shoshana Appleton - an Israeli who married a local lawyer, Ronald Appleton KC, in the early 60s - it provided company and cheer in a land thousands of miles away from where she was born.

“A culture shock is putting it mildly,” she says tersely.

“Nothing had ever happened here. Coming from Israel which was such a vibrant [place] and things were happening all the time to here…” her voice trails off.

“I thought I had come to the end of the world. I said to Ronnie, ‘Has nothing happened here since 1690?’

“Then, of course, he blamed me when things started happening and that’s when I began to feel a bit at home. It helped me acclimatise.”

In James Joyce’s Ulysses, the Rabbi boasts that “Ireland is the only country of which it could be said that they never persecuted the Jews.” Religion in Ulster has historically been a toxic divider, but Mrs Appleton says Belfast Jews have encountered nothing but respect from their neighbours.

“I think Northern Ireland is very tolerant,” she muses.

“The people here are very steeped in the Old Testament, they’re very religious in that sense.

“They love the Jewish people generally. So, up here in Northern Ireland we haven’t had much antisemitism, I must say.

“As someone once said, ‘Northern Ireland must be the best place to be a Jew because you’re neither a Protestant nor Catholic’ - unless you’re a Catholic Jew or a Protestant Jew.”

During the Troubles, Belfast Jews had an unofficial policy of keeping themselves to themselves. There were no prominent Jewish politicians or paramilitary members on either side, but most had little sympathy for the republican cause.

“The funny thing is that one of the commandments of the Jewish religion is that you honour the State in which you live,” community chairman Michael Black explains.

“So, we have a prayer which is said every week which is said to the royal family and the government. If you live in Dublin, it would be to the President and the Dáil.

“So, being good citizens, we would have not taken sides as such, but we’d have more sympathy with the government. Likewise, in Dublin they’d have maybe had more sympathy with the nationalists.”

Treasurer Stephen Grant is a child of the 1950s. Back then, there were well over 1,000 Jews in the city and the community had a cheder, its own scout group and a Hebrew school. The decades of violence gave many of those families a powerful incentive to pack their bags and never come back.

“Anybody who was in a profession, who could easily move would move,” he explains wearily.

“They moved to England, they went to university and didn’t come back. Israel they went to, the States - they just went everywhere.

“That accelerated the slow contraction of the community.”

Nowadays, the community sometimes struggles to assemble a minyan - or quorum - of 10 Jewish men needed for a Saturday service.

The current synagogue was built in 1964 and its ornate beams are shaped in the Star of David. As the community shrunk, the main room for worship was cut in two to provide a more intimate atmosphere.

“Most of the men here are in their 70s and 80s - I’m one of the younger ones and I’m 77,” Mr Grant adds.

“At the moment, we’re just about getting a quorum but sometimes it’s a struggle. Sometimes we’re at nine and that’s just slowly going to get worse over the next five years.

“We’ve still got this beautiful building here, our synagogue, which is lovely and I suppose in a few years’ time we’re going to have to think about what we do going forward.

“What can you do? We’re all getting past it and there are no young people coming up behind to take up the positions that are required.”

Such an eventuality would be a huge loss - not just to local Jews but to Ireland.

The Jewish community in Belfast dates back to the 19th century, when thousands of Jews fled the pogroms of Tsarist Russia to more tolerant nations in the west. Even a brief wander around the synagogue offers a glimpse into the history of not just Belfast Jewry but the whole of Europe.

The community’s founder, Otto Jaffe, was a German-born British subject, a Lord Mayor of Belfast and stalwart of the Unionist party. Despite the service of his son in the British Army, when the Great War broke out he was forced to move to England because of intimidation.

After the guns fell silent on the Western Front, Belfast’s Rabbi earned the nickname of ‘the Sinn Féin Rabbi’ during the War of Independence and his son, Chaim Herzog, later became President Israel. A plaque marking his birthplace was removed in 2014 because of local opposition to the policies of the Israeli government.

"This is quite sad for me and my family," his son, Issac, said at the time

"The history of my family has been intertwined with the history of Irish independence and the story of Belfast itself, which is a city with huge history and which I admire and adore.”

On the wall of the synagogue, a memorial topped with the Star of David commemorates worshippers who died serving King and Country in the World Wars and a plaque, bilingual in English and Hebrew, laments the loss of the ‘Martyred Millions of European Jews’ during the Holocaust.

A framed picture lists the unanimously agreed rules of the long since closed Derry Synagogue. Does the same fate await its Belfast counterpart? Doomed to dwindle until it has no more members and its possessions are pensioned off to a nearby congregation.

Rabbi Kale does not believe that is the case.

“We always say that where there is life, there’s hope,” he says.

“Where there is will, there’s a way.

“So, we don’t look at dying. The Jewish people could have died many times; they could have died at the time of the Holocaust, they could have died when they went into Egypt with Jacob.

“We do our best to maintain it and we always look forward to inviting visitors and to inviting newcomers and we welcome them as part of our family.”

The party ends with a statement of thanks for the organisers, there is a chorus of “Chag sameach” and a smattering of applause. Then the Jews of Belfast don their coats and disappear into the December darkness.

Main image: Rabbi Kale lighting the first Hanukkah candle.