The fishermen know that the sea is dangerous and the storm terrible, but they have never found these dangers sufficient reason for remaining ashore — Vincent Van Gogh

There is an inherent drive in man to venture away from home and explore beyond what we know. As we dispersed across the globe any mountain we met we climbed it, any desert we met we crossed it, and any ocean we met we sailed it. This drive to adventure led to multiple discoveries of North America through history. It was, however, Christopher Columbus’s trans-Atlantic voyage in 1492 which began the contact between the Old and the New Worlds which last to this day.

Following this ‘discovery’ of the Americas the powers of Europe launched themselves into a pell-mell rush to lay claim to their piece of these new lands. The massive empires of Spain and Portugal focused their efforts on the southern landmass with its obvious abundance of mineral wealth and productive climate, forcing the other powers to aim further north.

The northern landmass offered similar opportunities for wealth creation, though this wouldn't be so easily plucked from the ground. Very soon the islands and southern territories of North America found themselves dotted with the flags of European kings and emperors. This imperial expansion never stopped as powers vied for dominance of impenetrable jungles and barren snowscapes.

The search for a westward trade route to Asia didn't, however, stop with the discovery of a large landmass in the way. Though they were busy claiming new lands and establishing economies and industries there, the powers of Europe still strove to discover routes through or around this New World. While some would look for a passage that bisected the continents others looked north for a passage to mirror the southern Cape Horn.

It was the 1494 Treaty of Tordesillas which forced nations to risk ships and crews in the Arctic Ocean. This treaty split the known world between Spain and Portugal and as such gave these powers exclusive rights to the only open routes to Asia. Unable to officially explore or traverse Cape Horn or the Cape of Good Hope the other European powers began to seek out an uncontested route in the north, which would in time become known as the Northwest Passage.

The English led the charge into the frigid waters when, in 1497, Henry VII dispatched John Cabot with instructions to discover a route to China through the ice. Though this went against the Treaty of Tordesillas Cabot made landfall and became the first modern European to explore mainland North America. Though his mission to discover a sea route to Asia was a total failure Cabot had established the presence of inhabitable land.

The following centuries would see many follow in Cabot’s shoes as further expeditions sought out this increasingly mythical sea route. Yet many of these journeys were not taken in vain and a great many explorers during the 16th century came across and laid claim to new lands as they probed at the North American coast. As such the quest for the elusive Northwest Passage played a key role in establishing the political and national geography of North America which lasts to this day.

Searching out a route to Asia at the behest of King Francis I the explorer Jacques Cartier came upon the Gulf of St Lawrence. Between 1534 and 1542 Cartier undertook three voyages to the New World during which he navigated the St Lawrence and Ottawa Rivers, laid claim to these lands in the name of Francis, and helped established the first settlements which would eventually become New France. In a foreboding meeting Cartier planted a 10 meter tall cross before the native Iroquois; its inscription Vive la Roi de France looming over their land and people.

Behind Cartier followed the British explorers Martin Frobisher and John Davis. In 1576 Frobisher, a colourful character with a motley history of mercantilism and piracy, had finally raised the funds needed for a voyage in search of a passage to China. This had been an obsession for the dyed in the wool seaman for more than a decade. Yet his first voyage to the New World only served to whet his appetite and the interests of those at home as Frobisher returned with tales of the Inuit and chunks of, what later transpired to be, ‘fool’s gold’.

Frobisher explored the coast of Canada during two further voyages, this time part funded by Queen Elizabeth. Plumbing its depths for mineral resources and helping to try and establish English control of the region Frobisher embedded himself into the history of Canada. Frobisher’s naval activities extended far beyond exploration, however, and he was awarded a knighthood for his pirating of French shipping and naval engagement with the Spanish Armada.

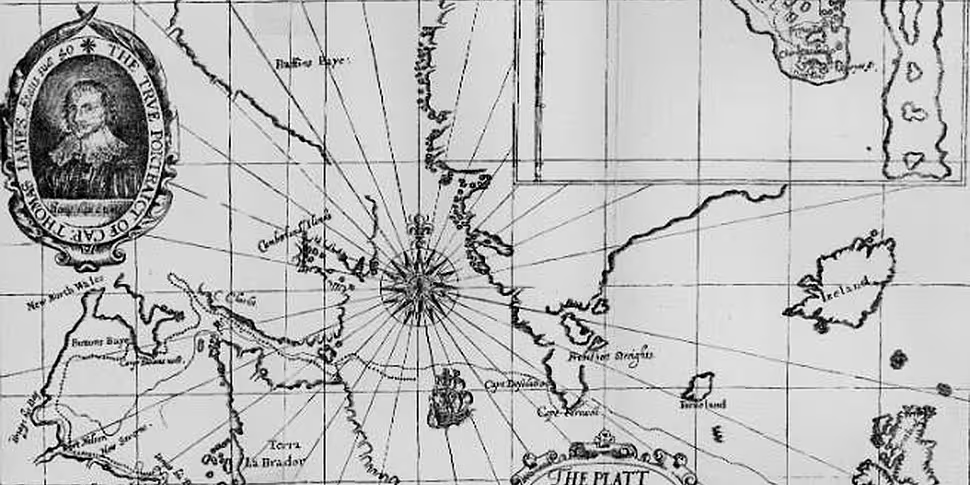

John Davis similarly helped to repel the vast Spanish Armada and, in 1591, followed Frobisher’s example by venturing in search of the Northwest Passage. Though he is most famous for his invention of the backstaff Davis also traveled and mapped the Davis Strait and Inlet. Together Frobisher and Davis established the beginnings of the English, and later British, settlement of Canada.

The most important figure in the early establishment of British Canada, however, was Henry Hudson. In 1610-’11 he undertook his second, and most important, journey in search of the Northwest Passage. Hudson had spent 1609 searching for a western route to Asia for the Dutch East India Company. He had, however, aimed too far south, some claim intentionally. In 1610, under English colours, he didn't make the same mistake.

Hugging close to Iceland and Greenland Hudson’s expedition struck the northernmost tip of the Labrador coast and discovered what they thought to be the beginnings of the Northwest Passage. Though time would show that they were right Hudson and his crew had no idea of the scale of the feat before them. Coming upon an open bay, Hudson and his crew were convinced that they had triumphed in their endeavour.

The expedition would meet with tragedy, however, as they became ice locked and were forced to winter on the bay’s shore. After the ice thawed Hudson planned to continue his search for a western exit and a route to Asia. His crew had other ideas and, after mutinying, marooned Hudson, his son, and seven other sailors by setting them adrift in a small boat. Though there was no further contact or word from Hudson his legacy was secured as the crew returned with his charts and maps. The bay that had been discovered was massive in its scale and, coupled with its large network of large estuaries, allowed access to a great deal of this new region increasingly becoming known as Canada.

The Hudson Bay was to become the central hub of British activity and interest in North America and became the focal point for all future searches for the Northwest Passage. While the area increased in activity thanks to the fur trapping of the Hudson Bay Company and British settlements started to crop up along the coast, adventurers and explorers continued to pass through the bay searching for the elusive Northwest Passage.

The next 300 years saw captains from various nations turn back from their search empty handed. Though many discoveries were made during this time and a large amount of the Canadian Arctic Archipelago was mapped the passage was all but dismissed as an impossibility thanks to the arctic ice.

In 1772 the English explorer Samuel Hearne trekked across the west coast of the Hudson Bay; proving that there was no route from the bay that would give access to the Pacific Ocean. Four years later the famous Captain Cook undertook a search for the passage. Together with the journeys of Captain George Vancouver in the 1790s it was determined that there was no possibility of a passage south of the Bering Strait.

There was, however, no letup in the search for the passage and the 19th century saw many more lives and ships lost to the search for a route through the ice and frigid waters. One of the most famous expeditions was that of Sir John Franklin. Setting off in 1845 the goal for Franklin, and the two ships under his command, was to chart some of the last 500km of unexplored Arctic mainland coast and search for a sea route to the Pacific in this area.

Both ships and all 129 hands, including Franklin, were lost to the arctic. In the time since the expedition’s disappearance numerous other ventures have searched for answers to what happened. It is reckoned today that both ships became icebound in September 1846 and the crew took shelter in the nearby King William Island. Over the next two years the crew succumbed to starvation, disease, and the arctic cold as they first tried to ride out the icy winter and then as they attempted to trek back to civilisation on foot.

The loss of the Franklin expedition was, however, an important piece in the puzzle to discovering the Northwest Passage. A well respected figure of high standing in British society the news of Franklin’s disappearance prompted others to venture in search of him. One such figure was Robert McClure who set off in search of Franklin’s expedition or any evidence of what befell them in 1850. Over the following four years McClure and his crew sailed, sledged, and starved their way across northern Canada.

Though no sign of Franklin was discovered during the voyage, in 1854 the McClure party became the first people to navigate the Northwest Passage as the Atlantic hove into view. Though they were unable to complete the journey by ship the McClure expedition had demonstrated that the Northwest Passage did exist and traversing it was possible. It would, however, take more than 50 years for someone to successfully navigate the passage as ice and the elements continued to block the way.

Despite British dominance of so much of the exploration and attempted exploration of the Northwest Passage the eventual first crossing was made by a Norwegian. The turn of the 20th century saw a great deal of activity as figures like Ernest Shackleton, Douglas Mawson, and Robert Scott explored the frigid Arctic and Antarctic. Greatest amongst these, however, was Roald Amundsen who led the first expedition to reach the South Pole in 1911 as well as the first expedition to undisputedly reach the North Pole in 1926.

Before all of this, however, Amundsen had earned renown for captaining the first expedition to successfully navigate the Northwest Passage. Setting off in 1903 Amundsen, and six other men, spent the next three years steering their modified fishing vessel, the Gjøa, through the various waterways of the Canadian Arctic Archipelago before emerging triumphant into the North Pacific in early 1906. His route wasn’t, however, viable for any but the shallowest of vessels and commercial shipping could never follow his trail.

The 20th century would, however, see the Northwest Passage become a topic of conversation for more than just the sailor or adventurer. Until now a viable Northwest Passage had been all but mythological. With Amundsen’s success this changed and as the century wore on more viable routes were discovered, larger ships were making the journey, and the crossing time was being greatly reduced. Coupled with this was the shrinking of the Arctic ice which had proved such a formidable obstacle until now.

The past 100 years has seen the world try to cope with and legislate for the existence of a viable commercial and strategic shipping route through the Northwest Passage. Through the Second World War, the Cold War, the coming of the new millennium, and the rise of the Asian economies the international community has tried to juggle the issue of the sovereignty of the Northwest Passage.

Today that issue still isn’t fully resolved and yet each year the passage is opened up more and more as the polar cap melts away. The Northwest Passage is still looking into an unknown future as we begin to face the issues of mineral rights in this region and the Arctic Ocean, the possibility of shipping through the area, and what all of this means for the indigenous people and local wildlife.

Listen back as Patrick talks with a panel of explorers, historians, researchers, and local experts about the history and the future of the Northwest Passage.