Love is our true destiny.

We do not find the meaning of life by ourselves alone—

we find it with another.

We do not discover the secret of our lives by mere study

and calculation in our own isolated meditations.

The meaning of our life is a secret that is to be revealed

to us in love, by the one we love.

We will never be fully real until we let ourselves fall in love….

Love is the revelation of our deepest personal meaning, value and identity.

-Thomas Merton

The 20th century was a time of massive upheaval around the world as global conflict accelerated already strong movements for change. Tastes, philosophies, trends, people’s ways of living and thinking were all changing from decade to decade and year to year. The Catholic Church was far from immune to this and as time marched on many people marched away from the Vatican’s outdated rule.

This issue was acute following the Second World War as people found their faith shaken by the horrors of the Holocaust and the awesome atomic bomb. Compounding this haemorrhaging of believers was the continuing Cultural Revolution spearheaded by jazz musicians and the Beat writers. The resulting explosion of Rock and Roll and Pop Culture would change the world forever and the Catholic Church was no exception to this.

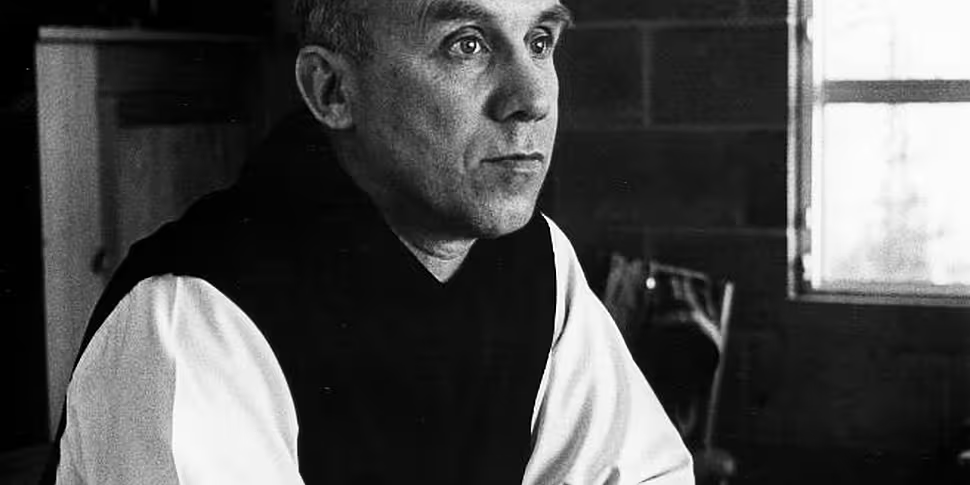

In reaction to the strange new world the Catholic Church held the Second Vatican Council to reassess and reform the Church and its philosophies in the modern world. While Vatican II instituted some of the biggest changes ever seen in the Church it was merely the crashing of a wave of reformative thought which had built up within the Church during the 20th century. One of the most important thinkers who drove this reformation movement was the Trappist monk Thomas Merton. A poet, writer, social activist, student of comparative religion, and unconventional thinker Thomas Merton was able to reconcile the Catholic Church and its doctrines with the quickly changing wider world. It was most likely his unconventional, excessive, and melancholic youth that made this convert into one of the most important Catholic thinkers of the 20th century as he spoke of Christian love in a way the new generations could understand.

One of the most important thinkers who drove this reformation movement was the Trappist monk Thomas Merton. A poet, writer, social activist, student of comparative religion, and unconventional thinker Thomas Merton was able to reconcile the Catholic Church and its doctrines with the quickly changing wider world. It was most likely his unconventional, excessive, and melancholic youth that made this convert into one of the most important Catholic thinkers of the 20th century as he spoke of Christian love in a way the new generations could understand.

Born in France in 1915 Thomas Merton was the first child of Owen Merton, an Anglican painter from New Zealand, and Ruth Jenkins, an American artist and Quaker. Baptised in the Church of England Merton’s early life seems to have been mostly agnostic and religion didn’t seem to be a source of solace for him after the death of his mother when he was just 6 nor during his tumultuous school years as he moved around between family members, schools, and continents.

The sense of loss and solitude brought about by the death of his mother, his father’s often absence, and his separation from his only brother and other family during his time in boarding school made Merton into a melancholic child. Though not devoid of friends this solitude and introspection surely informed the philosophies he would later become known for. More important than this, however, was Merton’s relationship with his father and his father’s approach to relationships and love.

After the birth of Thomas the family moved to New York. It was here that Merton’s mother died and it was here that Thomas’ brother, and later Thomas himself, would be left as his father travelled and pursued an affair with the writer Evelyn Scott. Though the affair was broken off because of the inability to reconcile Scott with Thomas and Owen moved to France with the children Thomas’ relationship with his father would remain distant as he was placed into a boarding school.

Though he attended church during his time in school Merton’s relationship with religion did nothing but deteriorate and even the news of his father’s brain tumour and resulting death didn’t reconcile the young Merton with god. Instead, as a teenage orphan with financial security, Merton embraced the rambling and artistic life of his late father. It was during a visit to Rome that Merton began his religious awakening. Inexplicably drawn to churches and religious sites Merton commented that he would like to become a Trappist Monk after visiting their Tre Fontane monastery. This brush with religion would fade, though as Merton failed to find the same inner fervour during his trips to churches in the States and back in England. In 1933 Thomas entered Clare College, Cambridge, and a dark and negative period of his life began. He began drinking and spending to excess and garnered a reputation as a philanderer. There are numerous rumours surrounding Thomas’ leaving of Clare College but what is known is that in 1934 he enrolled in Columbia University as a sophomore.

This brush with religion would fade, though as Merton failed to find the same inner fervour during his trips to churches in the States and back in England. In 1933 Thomas entered Clare College, Cambridge, and a dark and negative period of his life began. He began drinking and spending to excess and garnered a reputation as a philanderer. There are numerous rumours surrounding Thomas’ leaving of Clare College but what is known is that in 1934 he enrolled in Columbia University as a sophomore.

Merton found a welcoming home in Columbia and the move was certainly a key moment in his life. Here he met many of his lifelong friends and set himself on the course to follow the example of Gerard Manley Hopkins to convert to Christianity and become a priest. By the end of his studies in Columbia Merton was a Confirmed Christian and on his path to become an ordained priest of the Franciscan Order.

The path to priesthood would be blocked, however, by confessions of his past and it wouldn’t be until 1942 that Merton would be welcomed into the monastic life, though as a Trappist monk not a Franciscan as earlier planned. During his time learning his vocation Merton continued his writing, encouraged by his father superior. This amalgamation of spirituality and writing would catapult him to fame as his writings, especially his autobiography The Seven Story Mountain, struck a chord with post-war society. What may have enamoured him to the evolving society in the latter half of the 20th century was his interest in inter-faith spirituality. Of special interest to him were the so called Eastern philosophies and religions; Taoism, Buddhism, Hinduism, Jainism, and Sufism. Along with Christianity these topics dominated Merton’s time and thought and he corresponded extensively with others on matters of faith and spirituality.

What may have enamoured him to the evolving society in the latter half of the 20th century was his interest in inter-faith spirituality. Of special interest to him were the so called Eastern philosophies and religions; Taoism, Buddhism, Hinduism, Jainism, and Sufism. Along with Christianity these topics dominated Merton’s time and thought and he corresponded extensively with others on matters of faith and spirituality.

While he continued his writings from the monastery Thomas Merton strove for leave to venture internationally. In 1968 this was granted and he toured Asia on a spiritual journey. There he met and spoke with the Dali Lama, the Japanese author Daisetsu Teitaro Suzuki, and the Vietnamese monk Thich Nhat Hanh. He was commended for his knowledge and understanding of Eastern religions by those he met and became one of the most important figures in bringing understanding between Eastern and Western philosophies and encouraging interfaith dialogue.

This was all to prove ill-fated for Merton, however, as he died after speaking at an interfaith conference between Catholic and non-Catholic monks in Bangkok in December 1968. Though some question the circumstances of his demise the official account is that he was accidentally electrocuted after stepping from his bath. On his death he was one of the most progressive and important Catholic thinkers and writers of his time and is still one of the most important figures in 20th century spirituality and interfaith understanding. This Sunday ‘Talking History’ takes a look at the fascinating life of Thomas Merton and assess the importance and legacy of his writings. Find out about his exciting and emotional youth, his enlightening studies and writings, his dedication to pacifism and social reform, and his love of people—especially women. Did he father a child in his youth? Did he fall in love with a nun while recovering in hospital? Was the end of this fantastic life a simple accident or something more? Listen back here to find out.

This Sunday ‘Talking History’ takes a look at the fascinating life of Thomas Merton and assess the importance and legacy of his writings. Find out about his exciting and emotional youth, his enlightening studies and writings, his dedication to pacifism and social reform, and his love of people—especially women. Did he father a child in his youth? Did he fall in love with a nun while recovering in hospital? Was the end of this fantastic life a simple accident or something more? Listen back here to find out.