This week we learned the St Patrick’s Day destinations for Government Ministers and as usual the Taoiseach will be paying a visit to the US President in Washington DC.

An issue that has earned an almost permanent spot on the agenda for their annual meeting is that of the undocumented Irish living in the United States.

But what about the undocumented workers living here, in Enda Kenny’s own backyard?

The facts

The Migrants Rights Centre is to address a Justice Committee on a proposed scheme to help regularise this area - as an estimated 26,000 undocumented migrants living in Ireland.

Many of these people are living in Tralee, Kilkenny, Ennis, Navan and larger urban areas. The overwhelming majority (81 per cent) have been in Ireland for five years or more and 21 per cent have been in the country for more than 10 years.

Some 86.5 per cent entered the country legally and subsequently became undocumented.

A similar percentage (87 per cent) are working and more than half have a third-level education.

The five most common nationalities among undocumented people living here are: Filipino, Chinese, Mauritian, Brazilian and Pakistani.

The reality

Helen Lowry is the Community Work Coordinator with the Migrant Rights Centre and explained how those living in legal limbo are in a constant state of fear and anxiety.

"People are in constant fear - in terms of being unable to report a theft, serious injury or a serious criminal offence and just generally being nervous if there's a knock on the door.

Despite that fear, some of those people were willing to come forward and share their stories.

Jason from The Philippines

Jason’s story is one that is repeated time and time again in this community. In 2004, He came here on a holiday visit and applied for a job when he was here. His employer told him that he would formalise everything, apply for a full work permit and keep everything above board.

Months passed and there was still no sign of this work visa. Jason kept asking and kept being told that it was coming. Meanwhile he was doing maintenance work and cleaning work for about €2/3 per hour. Eventually months turned to years and he was essentially told: 'You won’t get a visa and if you complain about me, you’ll be deported so just stay quiet.'

Jason's main incentive for coming here was because he has three kids at home and if he stayed there, he couldn’t put them through school or college. In Ireland, even on a low wage, he can send money back to them. He has two daughters - one is now a midwife and one is working in IT. His son is training to be a pilot.

But in the 11 years he has been here, he has only seem them on a computer screen. Last year he watched his father's funeral via Skype which he describes as a "knife going through my heart". He apologises as he breaks down when he says that the first thing he would do, should he be granted a visa, would be to go visit his family.

The younger undocumented

While Jason's children are in their early twenties there are different challenges for those undocumented who give birth to children inside Ireland. The legal limbo is passed down to the next generation as they are unable to obtain PPS numbers - which is manageable in primary and secondary school but when it comes to attending higher level education they are viewed as international students and charged the subsequent fees. With their parents on low income jobs, covering the cost is just not viable. The only option is for them to go into similar low-wage employment.

Rebecca from India has been here for over 10 years and her children have been here that whole time. Her daughter has just completed her leaving certificate, all honours, and had her choice of CAO courses but her whole life is just left on pause which her mother explains is very difficult for her to comprehend.

"She thinks Ireland is her home," Rebecca points out. "All the undocumented youth they are all mixed with the Irish society and all their friends are Irish and they think they are Irish... it is very hard for them to live like this."

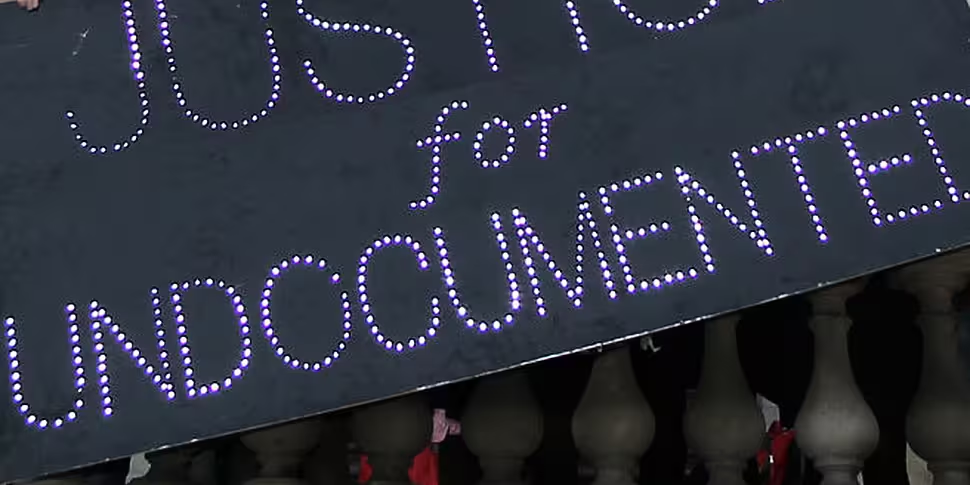

The US irony

Rebecca;s argument and the emotion portrayed by Jason are all too similar to the predicaments laid out by Irish people living in the US. For decades, Irish governments and various Taoisigh have lobbied for those people to be regularised, which is something the Migrant Rights Centre is putting to the Oireachtas committee today.

Naturally, some people will be incensed - fearing it will lead to open borders - which is not the case at all, as Helen Lowry explains: "We would expect a number of criteria such as the length of time in the country. Someone who is here for a minimum of four years should be allowed to apply, potentially less with children.

"We predict that this could bring in substantial revenue for the country should their situations be regularised."