Barbara Feeney will let Sean Moncrieff rifle through her scrapbooks today, as she once again takes him on a tour of her #StationeryCupboard.

Tune in live to Moncrieff at 2.45pm: http://www.newstalk.com/player/

While we may think of scrapbooks as a pre-Internet place for pictures of fluffy cats to be collated and preserved, it wasn’t always that way.

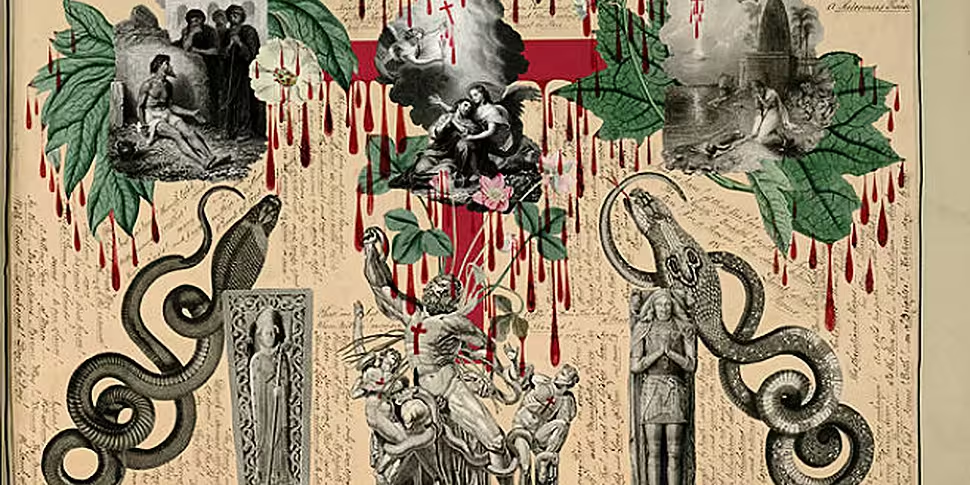

Evelyn Waugh’s Blood Book is not the best known piece of literature the British writer is known for, but that’s hardly surprising – it’s not a work of fiction, nor did Waugh produce it. But his name is attached to the curio of Victorian Britain, because he was taken by this scrapbook’s macabre collection of images that he bought it in 1950, and that’s the only reason why it’s still around today.

The Blood Book, so called because of the red Indian ink liberally splashed over the pages to make it look like the collection of decoupaged images are bleeding, is inscribed at the start by John Bingley Garland to his daughter Amy. Written on September 1st, 1854, Garland writes: “A legacy left in his lifetime for her future examination by her affectionate father.” The post seemingly came a year before Amy married, so archivists at the Harry Ransom Center at the University of Texas at Austin, believe it was probably a betrothal gift from father to daughter.

While we might think of scrapbooking as a niche pastime today, it was extremely common in the 19th century, typically a woman’s occupation involving clipping newspaper articles and lovingly sticking them into books. The Blood Book, though, appears to have been entirely assembled by John Bingley Garland, a respected businessman who went on to become the first speaker of Newfoundland’s parliament.

That it was produced by a man is not the only odd thing about the book, which contains several hundred images, some of which were taken from books on the etchings of the poet William Blake. While the images seem bizarrely visceral to modern eyes, Garland’s descendants saw it a different way. Rich Oram, associate director of the library where it is stored, writes that they said: “It is a precious reminder of the love of family and Our Lord.”

[All Images: Harry Ransom Centre]