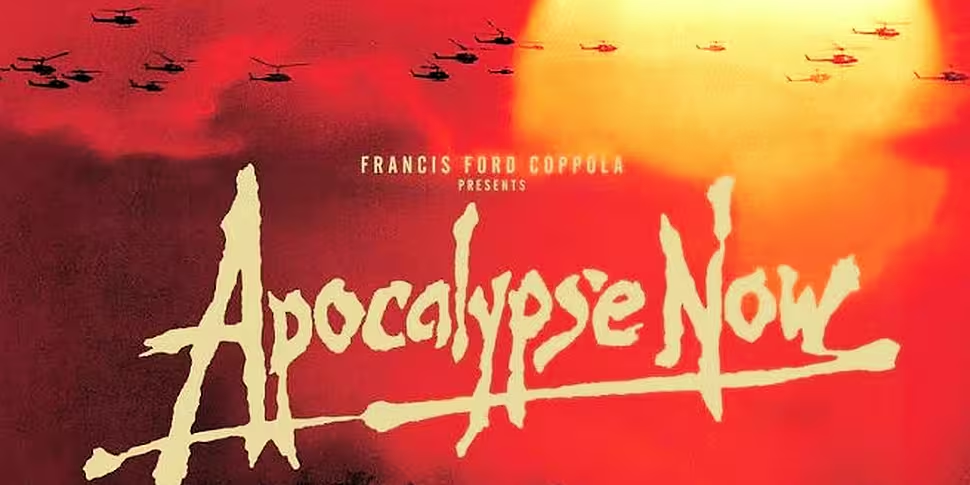

The blades of the helicopters audibly slap the air as they fly in low over the open water. The orange sun at their backs sends their shadows racing ahead. Suddenly the sky erupts in Wagner’s Ride of the Valkyries, the booming tune terrorising those on the ground as the Vietnamese village and surrounding jungle are consumed in waves of napalm, rockets, and gunfire. On the beach American soldiers surf among falling mortar rounds.

Since its release in 1979 Francis Ford Coppola’s Apocalypse Now has had a massive impact on today’s popular perception of the Vietnam War. This scene in particular informs a great deal of our accepted vision of this conflict with its image of boys who’d rather surf than fight flying into combat for the amusement of an officer who laments that ‘someday this war is going to end’. Yet the making of this movie is as compelling as the story it tells.

Clip of Major Kilgore and troops on the beach

Though Conrad’s Heart of Darkness is set in a time long since passed, its exploration of man’s most base nature and the effects of unchecked power have kept it relevant and alive. In the 1960s and ‘70s this tale of colonial corruption resonated with those who saw America’s involvement in Vietnam reflected in Marlow’s journey and the tyrannical figure of Kurtz. The movie industry wasn’t exempt from this interest and in 1969 John Milius decided to adapt Heart of Darkness for a Vietnam War movie commissioned by Francis Ford Coppola.

This modern retelling sees Captain Benjamin Willard fill the role of Charles Marlow as he ventures downriver to the waiting figure of Kurtz, now an out of control US Special Forces Colonel. While Marlow’s official relationship with Kurtz is benign, however, this retelling sees Willard tasked with terminating the rogue Colonel ‘with extreme prejudice’. This promised confrontation makes violence the central theme of this modern version as Willard shows us the various theatres and spectacles of the Vietnam War as he floats ever closer to Kurtz.

The original idea was to film the movie in Vietnam while the war was still going on; mixing footage captured from real combat with scripted scenes shot on-site. Not surprisingly it was hard to find a studio interested in financing such a project. In 1974 Coppola began to look at the project in a more traditional and viable light. Over the next two years he reworked Milius’ script, gathered funding together, and arranged for the film to be shot in the Philippines.

Poster for Apocalypse Now

Poster for Apocalypse Now

Though many actors had been approached for the leading role the intensive shoot schedule and prolonged isolation in the Philippines saw most pass on the opportunity. A fee of $3.5million had secured Marlon Brando for the role of Kurtz and eventually Harvey Keitel signed on as Willard. With a budget of around $13million, the cooperation of Philippines’ President Marcos, access to cheap labour, and a tight production schedule Coppola began to shoot Apocalypse Now in March 1976. It started to fall apart soon after.

After reviewing the first shots of Keitel it became clear to Coppola that he wasn’t suited for the role of Willard. Martin Sheen was flown in as a replacement and filming began anew with the previous weeks’ footage scrapped.

Though a risky move this decision would prove vital in making Apocalypse Now the success it is today. Soon after Sheen arrived, however, so too did Typhoon Olga. The high winds and torrential rain not only put a stop to filming but also severely damaged a number of key sets that now needed to be rebuilt.

The Philippines had seemed the perfect location for filming. Not only was it similar to Vietnam but America’s support for President Marcos meant that the Philippines’ armed forces used the same equipment as the US in Vietnam. Coppola had come to an arrangement whereby helicopters, pilots, and other personnel would be made available for filming unless they were needed to fight the communist rebels. The disruptions to shooting caused by helicopters being called away and constantly changing pilots further delayed the filming and soon the original budget had been exceeded.

Martin Sheen as Captain Benjamin L. Willard

Martin Sheen as Captain Benjamin L. Willard

As Coppola was forced to pump his own money into the project further delays and complications were added by the antics of the cast and crew. Soon the newspapers began to sardonically ask ‘Apocalypse When?’

Martin Sheen had been reluctant to sign on to the project. At 35 and out of shape he was wary of trying to keep up with the strenuous workload in the tropical heat. He was, however, also in a dark place and battling his own demons, specifically alcoholism. As filming went on Sheen seemed to become increasingly consumed by the role of Willard, journeying deeper into his own dark nature as Willard drifted downstream. This personal journey reached its zenith during the filming of the movie’s opening scene.

With its exploration of man’s more feral nature Coppola decided to open Apocalypse Now with Willard recovering from the night before in a Saigon hotel room; his manner and narration telling us about the cost he paid for his first tour and his addiction to the war. Filming for this scene was on Sheen’s 36th birthday and he had been drinking heavily before the shoot. As Coppola began to direct him Sheen became increasingly agitated and soon put his fist through a mirror.

Coppola called for medical aid after it became clear that Sheen had badly cut his thumb. Sheen, however, insisted on continuing the scene and it soon became clear that he was tackling his own demons in front of the camera. Coppola kept the filming going and captured the tension and energy of the room. Though Sheen had managed to capture Willard perfectly the cost for this performance was terribly high. In early 1977 he had a severe heart attack and the production was once again derailed as they waited for their leading man to return.

Marlon Brando as Colonel Walter E. Kurtz

Marlon Brando as Colonel Walter E. Kurtz

While Sheen seems to have been subsumed into the character of Willard during film the same cannot be said for Marlon Brando. With Brando widely regarded as one of history’s greatest actors securing him for the role Kurtzhad been a coup for Coppola, though an expensive one. The only stipulations had been that Brando read Heart of Darkness and slim down so as to better capture Conrad’s gaunt and haunted Kurtz.

After he arrived on site, however, it soon became clear that Brando had done neither. He was visibly overweight and almost totally unfamiliar with the story. Coppola had long been unsatisfied with the written ending and was constantly redrafting different iterations of it. This latest setback forced him to rethink the ending again and to shoot it in a way that would accommodate Brando and reconcile his size with the character of Kurtz. Coppola and Brando withdrew together to recast the ending and acquaint Brando with Heart of Darkness and his character.

In the end it was decided to keep Brando dressed in slimming black and shoot him shadow and smoke. To compensate for Brando’s unfamiliarity with Kurtz and the lines they decided to just shoot him delivering a series of impromptu monologues and piece his performance together from that. The end result was a mystical figure shrouded in secrecy and madness; his shadowy face, insightful ramblings, and grisly demise capturing the essence of the character that would have been lost otherwise.

The Doors, This is the End

The filming suffered even more mishaps and setbacks and by the time it wrapped in 1977 Apocalypse Now was over double the original budget and many months past schedule. Yet all of this madness seems to have been the key to the movie’s success; as Coppola put it: ‘[Apocalypse Now] is Vietnam. It’s what it was really like...We were in the jungle, there were too many of us, we had access to too much money, too much equipment, and little by little we went insane.’

In May 1979 Francis Ford Coppola brought the as yet unfinished Apocalypse Now to the 32nd Cannes International Film Festival. Screened as a ‘work in progress’ it was met with an enthusiastic response from patrons and critics alike and it was awarded that year’s Palme d’Or alongside Volker Schlöndorff’s The Tin Drum. The final cut was released later that year. Since then Apocalypse Now has come to be regarded as one of the greatest films ever made and in 1991 a documentary on its making was released.

Listen back to ‘Talking History’ as Patrick talks with a panel of historians and film experts about Apocalypse Now. Was the set really an almost constant party with drink and drugs abound? Was there actually a plan to use real cadavers as props? What has the lasting legacy of this movie been? And can we really count it as one of the greatest films ever made?