Fifteen men on the Dead Man's chest,

Yo-Ho-Ho and a bottle of rum!

Drink and the Devil had done for the rest,

Yo-Ho-Ho and a bottle of rum!

Victorian Britain is today remembered as much for its literature and fiction as anything else and, whether in their original form or through works they have inspired, the characters and tales conjured up by authors of this period still surround us. While Bram Stoker's Dracula set a high bar for horror fiction and Arthur Conan Doyle and Lewis Carroll set new standards for the detective novel and children's literature, one Scotsman laid down a model for the adventure story that would endure till today.

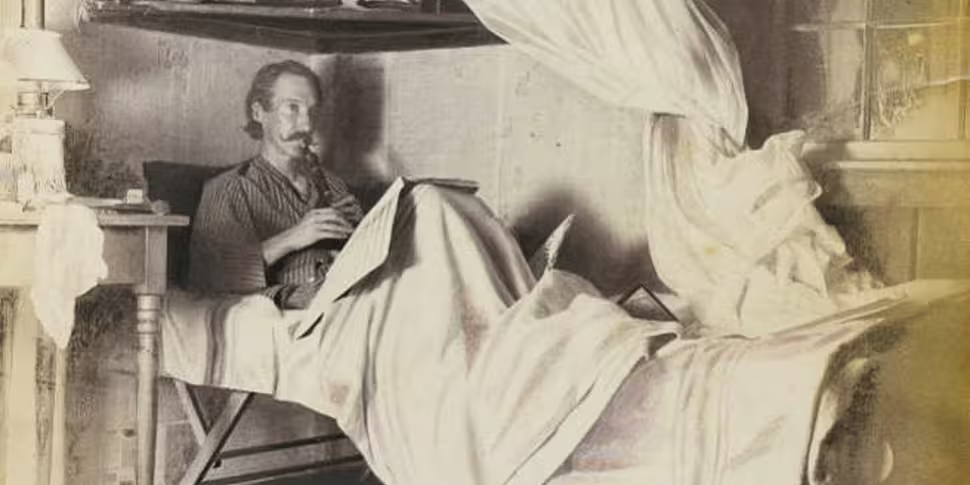

Today Robert Louis Stevenson is remembered most for his stories of swashbucklers searching for pirate's treasure, heroes gallivanting around the realm adventuring against wickedness, and a poor reasonable man at war with his inner animal desires. Yet his own life was more amazing than the tales he brought to life through the written word.

Stevenson was born in Edinburgh in 1850. A sickly child the Scottish weather didn't help his frail constitution and for most of his youth Stevenson was tended upon by his nurse Alison Cunningham. While this weak health would persist throughout his life it was most noticeable during Stevenson's childhood and prevented him from properly attending school; as a result a great deal of his early education was at he hands of private tutors. Though this stunted the young Stevenson's learning it didn't impact on his imagination and he recited his own tales to his mother and nurse before he himself was able to read.

While this predilection for storytelling is reckoned to have been inherited from his mother's father, a minister in the Church of Scotland, Stevenson's own father was also important in his son's literary development. Thomas Stevenson, much like his son Robert, had been an avid writer in his youth. Yet unlike Robert, Thomas would find no support at home for these enterprises as his father scolded him for this 'nonsense'. Engineering, specifically lighthouse engineering, was the family business and Thomas was lashed to that fate by his father.

When Robert showed the same enthusiasm for writing that he had had as a boy, Thomas eschewed his own father's example and was quick to support his son's endeavours. In 1866 Thomas paid for the publication of his son's account of the covenanters' rebellion on the 200th anniversary of the event. The Pentland Rising: A Page of History, 1666 was Robert Louis Stevenson's first published work. This supportive attitude would be very important in Stevenson's decision to forgo the engineering path trod by his father and uncles and instead pursue a life of letters.

Despite his love of writing Robert Louis Stevenson entered the University of Edinburgh in 1867 as an engineering student. For the next four years Robert would feign interest in this subject as he dodged lectures and joined his father on summer tours of lighthouses; which were enjoyed more for the journey and experiences gained than from any engineering interest. Despite the lack of interest in his main area of study Stevenson's time in college was not wasted. Friends, colleagues, and the University's Speculative Society fed Stevenson's artistic appetite and would stand to him in his post college years.

A great change was to come in 1871 as Stevenson told his father that he had no wish to become an engineer and rather desired to make his living from the written word. His father took this news well and endorsed his son's decision. He did insist, however, that Robert should study law and take the Scottish bar so that he might have some security in life. Robert returned to Edinburgh University later in 1871 to study law, but this second stint at college would be drastically different from his first.

Loosed from his familial ties to lighthouse engineering Stevenson embraced the rebellious Bohemian movement and all its trappings. During his time studying engineering Robert had grown close to his cousin Bob whose decision to study art had helped pave the way for the younger Robert to also break with family tradition. Together both boys moved further and further away from the Calvinist world in which they had been raised to embrace the chic fashions of the Bohemians. With their hair worn long and sporting velveteen jackets both of these Stevensons declared themselves atheists and, like many Bohemian youths, railed against the teachings of their forbears.

Though this behaviour caused a rift between Robert and his parents it was not done gleefully and his parents maintained the allowance on which he depended. While this allowance was important to Stevenson's continued studies and active social life it became even more important after his studies were finished. Though he was called to the Scottish bar in 1875 Robert would never practice law and later that year began his adventures which would rival and inform so much of his literary works. While the continued financial support of his parents allowed Stevenson to avoid practicing law and pursue his dream after college, it would prove far more vital in his later life.

During his college studies Stevenson's health failed again and he was sent to France in the hopes that the warmer climate and cleaner air might help with his ailment. So enjoyable was his time spent in France that Stevenson returned on several trips. The most important of these came in 1876 when Stevenson, fresh out of college, ventured down the waterways of Belgium and France with his friend Walter Simpson. This time canoeing from Antwerp to Paris was vitally important in Stevenson's life not only as the basis for his first real book, An Inland Voyage published in 1878, but as it introduced him to Fanny Van de Grift Osbourne, the woman that would change his life.

Fanny was ten years Roberts senior and had three children from her first marriage when she met the young Scotsman; though she was to lose her youngest, Hervey to tuberculous in 1876. Though their initial time together was brief the strong willed and quick witted Fanny left a fierce impression on Stevenson and when he returned to Paris in '77 they began to live together as lovers. Fanny's importance in Stevenson's life was only matched by his own parents and her children, especially her son Lloyd without whom a number of seminal Stevenson works might never have been including Treasure Island.

In 1878 Fanny returned to her husband, Sam Osbourne, in California. Though he at first remained in Europe, by 1879 Stevenson had determined to reunite with Fanny and took passage to New York without any word or hint to his family. For the fiscal savings and sheer adventure Stevenson journeyed second-class across the Atlantic. Though this passage caused his health to decline Stevenson pushed on and took a train from New York to California. Stevenson arrived in the Golden State penniless and on death's door.

Though Stevenson had recovered his health and was supporting himself and his writing through laborious work 1880 saw him invalided again as his health took another turn for the worse. This time, however, Stevenson had the support of Fanny, now divorced from Osbourne, and his parents, who supplied him with an annual allowance of £250. With his health restored and being reasonably financially secure Stevenson proposed to Fanny and they were married in May 1880.

After honeymooning in Napa Valley the newlyweds, and Fanny's son Lloyd, returned to Europe. The 1880s would prove to be Stevenson's most creative decade as Treasure Island, Kidnapped, and Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde all sprang from from his pen during this period. Although his literary star was in the ascendancy at this time Stevenson was unable to avoid the ill health that plagued. Despite moving numerous times Stevenson was unable to find anywhere in Europe or Britain that could provide him permanent respite. So, after his father passed away in 1887, Stevenson moved himself and his family, including his mother, to America.

Though far from insignificant this move to America would prove fleeting and the following year the Stevenson household set off together to cruise the South Pacific. In the islands of the Pacific Ocean Stevenson found his spiritual home. From 1888-1890 the Stevensons hopped from island to island adventuring the whole while. In Hawaii they became acquainted with and spent considerable time with King KalÄkaua and Princess Victoria Kaiulani. Stevenson became similarly close with the ruler Tembinok' over the months spent on the Abemama atoll.

It was, however, on the Samoan island of Upolu that the Stevensons settled and where Robert would see out the rest of his days. Though his greatest works were already behind him Stevenson's literary career continued during his travels and in his new exotic home. The biggest change in this period is the collaboration between Stevenson and his step-son, Lloyd Osbourne, as they begin to publish co-written works. Stevenson's own work of non-fiction, In the South Seas, gathers together many of his tales and exploits from the voyages as well as a great deal of his essays and articles from the period.

During his voyages Stevenson had cultivated a great affinity with the local people and a dislike of the harmful rule of the incompetent European officials. As a result Stevenson became increasingly involved in public life in Samoa. He adopted the Samoan name 'Tusitala', which roughly translates as 'Storyteller', and in 1892 published A Footnote to History. This scathing account of the Samoan Civil War and European complicity in this conflict helped to reform British policy in the Pacific and resulted in the recalling of two officials.

The next four years were fantastic for Stevenson as he found himself generally in good health and kept busy with work on his own estate and with the wider Samoan community. Though his literary output dwindled during this time 1893 saw Stevenson begin work on what he would regard as potentially his greatest work, Weir of Hermiston. Stevenson would never complete this work as died of a cerebral hemorrhaging on the 3rd of December. He was reverently buried on Mount Vaea where he might overlook the sea, he was 44 years old.

Despite his short life Robert Louis Stevenson had a phenomenal impact on the world. In literature his stories for young boys set a mold for adventure writing which still lasts today while his seminal works are still copied and imitated. There are few popular representations of pirates that do not carry shadows of Long John Silver and Treasure Island. In his own life Stevenson was so loved that a path was cut through the thick undergrowth by the local Samoans so that they might be able to carry him to his final resting place overlooking the sea.

Listen back as Patrick will talk with a panel of experts about the life and legacy of Robert Louis Stevenson. How true are the stories about this rebellious Scottish ladies' man? Was his life as adventurous as history has made out? How important was Fanny and her son Lloyd to Stevenson and his writings? And, most importantly, what has his true impact on the world actually been?