On today’s Moncrieff, astronaut Ron Garan's discusses his book The Orbital Perspective. Ron has spent 178 days in space, and his time on board the International Space Station had a profound impact on him. In the book, Ron discusses what we can learn about Earth from looking down from space, and indeed what successful space missions can teach us about life on Earth.

Ron talks to Sean at 3.45pm. As always, you can listen live at newstalk.com.

One of the subjects of the book is international co-operation in space, with Ron saying working work side by side with people from many different nationalities gave him a new perspective on many of the problems we face today. On the book’s website, the publishers explain that “if nations can join together to build the most complex structure ever built in space, imagine what we can accomplish by working together to overcome the challenges facing us all here on Earth.”

One of the very first significant co-operative missions in space took place in July 1975, when US astronauts and Soviet cosmonauts worked together on a mission for the very first time. This came about as a result of détente: the attempts made to ‘relax the tensions’ between the US and Russia during the Cold War. The so-called Space Race of course had been one of the defining ‘battles’ of the Cold War, with both superpowers attempting to best each other in terms of space exploration and technology. Both countries had enjoyed significant victories - while the US put the first man on the moon, cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin was the first human to reach space.

The Apollo–Soyuz Test Project inevitably didn’t get off the ground (literally) without some concerns and criticisms. Both sides had been known to criticise each others spacecrafts designs, while NASA face difficulties appropriating the funds for the mission - indeed, the huge budgets previously allocated to US space exploration missions were no longer sustainable from the 1970s onwards. There were practical concerns as well. In their history of the mission, NASA explains language was a significant issue, and “to alleviate this problem as much as possible, the Americans learned Russian and the Russians learned English. It was found that the best scenario was for the Russians to speak English and for the Americans to speak Russian.”

The liftoff of the Saturn IB launch vehicle (SA-210), for the Apollo/Soyuz Test Project (ASTP) mission. Image: NASA

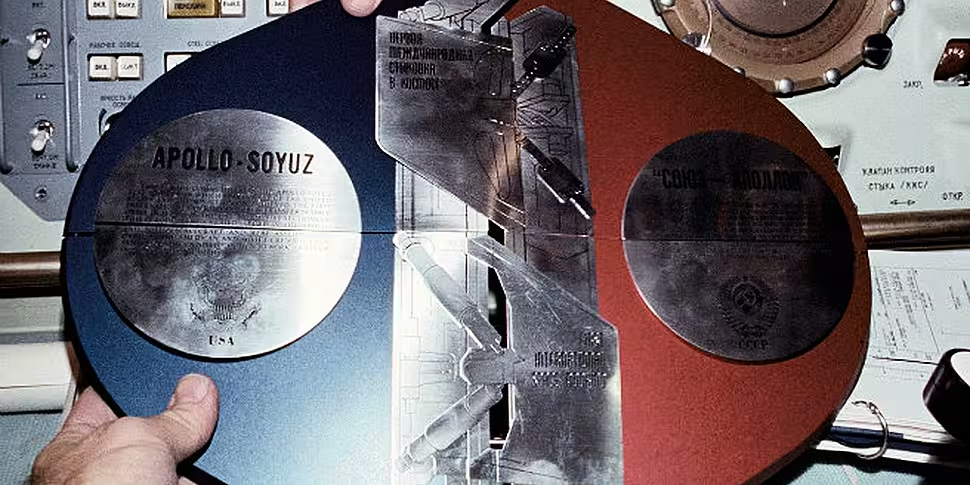

The two superpowers worked together on co-developing a docking module, allowing their different models of spacecraft to successfully dock while in orbit.

Soyuz 19, carrying two cosmonauts, launched on July 15th from Baykonur Cosmodrome, while the Apollo 180 launched from Kennedy Space Station seven and a half hours later with three astronauts on board. More than 50 hours into the mission, the two spacecrafts successfully ‘hard docked’. Cosmonaut Aleksey Leonov announced, "Perfect. Beautiful. Well done, Tom. It was a good show. We're looking forward to shaking hands with you in board [sic] Soyuz."

And shake hands they did, offering a memorable symbol of the progress that had been made in relations between the two nations:

The teams spent two days - including almost twenty hours of joint activities and transfers - including carrying out four different experiments, such as one that analysed the effects of weightlessness on fish eggs during their development. Much of the mission was broadcasted on television for both US and Soviet viewers, with the astronauts speaking Russian and the cosmonauts communicating in English. The crews ate together, explored each others’ crafts, exchanged gifts (including certificates and flags) and took part in other activities alongside their scientific efforts.

After undocking to capture more pictures for television - including having Apollo block the sun to create what NASA calls “the first man-made eclipse” - the ships briefly redocked before finally parting ways at 11:26 am EDT on July 19th. The Soyuz crew remained in obit for 30 hours before returning to Earth, while the Apollo crew returned on July 24th. The Apollo crew had been exposed to dangerous fumes during their descent, and were hospitalised for two weeks following their successful landing.

A view of the Soyuz 19 spacecraft as seen from the Apollo CSM flying the Apollo Soyuz Test Project in July 1975. Image: NASA

Overall the mission was considered a success by both nations, and helped pave the way for future international missions in space. Significantly, it also ended up being the final mission for NASA’s Apollo spacecraft and Saturn IB rocket.

After the conclusion of the Cold War, Russia and the US co-operated on the Shuttle–Mir Program in the 1990s, and they are two of the nations involved in the ongoing International Space Station mission. A 43rd Expedition of astronauts is currently active on board the ISS (Ron Garan was part of expedition 27 and 28, in 2011).

The Apollo–Soyuz Test Project undoubtedly paved the way for many significant space missions, and perhaps above all showed what could be achieved when countries worked together rather than against each other. It will be fascinating to see what further international co-operation can achieve in the coming decades, in space and on Earth. As Ron Garan proposes in his book, nothing is impossible...