Two months before school started in September of 2001, I had moved to Seattle, Washington and barely spoke English.

I was a Spanish immigrant and I felt it. America was to be my new home, but all I did was feel foreign. I can still feel the embarrassment I experienced when, in trying to say something was “stupid,” I said it was “silly” instead, after a dictionary led me astray. It doesn't sound like much, but for a 12-year-old girl who was new in town, it was mortifying.

The morning of September 11th, I got into my carpool car, the same as any other morning. As I got inside, my fellow carpool passenger exclaimed “can you guys believe what happened?”

“What?” I said.

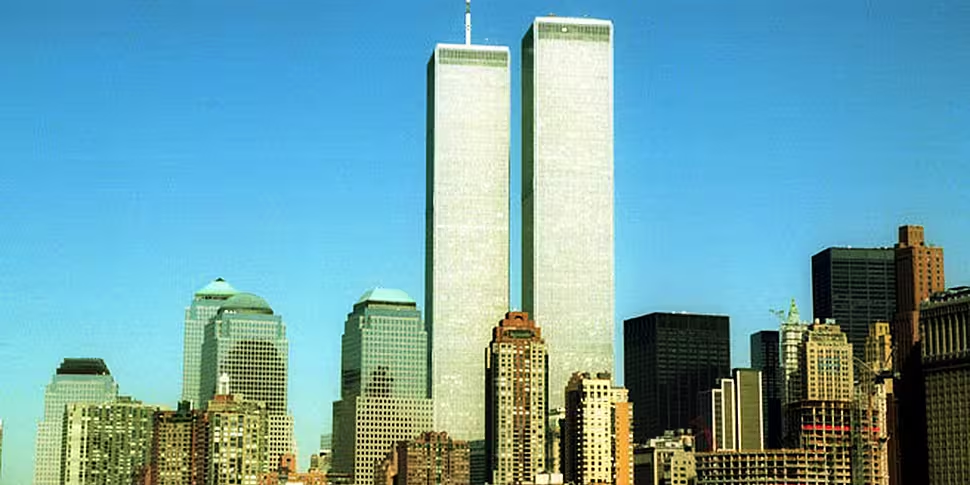

“Two planes hit the World Trade Center.”

“What’s the World Trade Center?” I asked, not realizing how ridiculous a question it was.

“You know, the Twin Towers.” Oops. Even I, foreigner and all, knew what those were.

Over the next hours we saw the towers crumble, learned of two more planes, of more deaths, of more horrid details. I was scared, but the magnitude of what had happened escaped me, much like I imagined it did for many other 12-year-olds. The embarrassment I felt anytime the words “World Trade Center” were mentioned - reminding me of the carpool incident - intensified.

During the next few days, we had countless school assemblies about 9/11; moments of silence for the victims, moments of silence for the first responders, discussions of what terrorism meant, discussions of what patriotism meant. Americans love assemblies. I could hardly understand them, but I was able to understand the sadness, the fear, the hopelessness and the destruction.

Slowly but surely, I internalized it. I pictured what would happen if a plane came crushing through my bedroom window, or my parents’ bedroom window. For a while, it was the only thing that I thought about.

At school, we carefully combed through the stories of the brave people who sacrificed their own lives to save others in the wreckage, of men calling their wives from their cellphones to tell them they loved them before the plane hit. How terrible it all was. Weeks later, we started talking about the 'why' of it all. In the playground, in the classroom, in the damn assemblies. It’s all we could talk about.

When one teacher opened up to the room asking for answers, I found myself raising my hand for some reason. I began to answer, unknowingly borrowing a line from the President, as kids often do, repeating what they hear on TV or from adults in a matter-of-fact manner:

"They attacked us because they hate our freedom. They attacked us because we are American," I said.

The teacher nodded with approval. I felt relief at the fact that my accent didn’t betray me too much.

Later, on the carpool ride home, we discussed what had transpired in class, and it hit me: I didn’t feel foreign anymore. I was part of a nation that had been attacked, wounded and maimed. A nation united against the injustice that had been carried against it. I was part of a nation that was morning, that was angry, and that loved school assemblies.

Esther Cohen, originally from Spain, is the US Social Media Editor for The Next Web.