The word 'cinematic' is often considered a very dirty word when we're talking about video games. But the new game Virginia - from co-directors based in Dublin and London - embraces the language of cinema in a very bold and refreshing way.

Often, 'cinematic' is used to sneeringly refer to blockbuster experiences such as the Uncharted series - big budget games with lavish production values and straightforward, action-packed gameplay.

Sometimes, 'cinematic' is a description used to refer to full motion video or FMV games - games based heavily around live action video footage. Older games in the 'genre' - I use the term loosely - have, by and large, struggled to age well, often cursed with low quality production values, limited interaction and incredibly cheesy acting. Such games fell out of fashion for a decade or so, but they have had a minor resurgence in recent years, thanks in particular to the acclaimed Her Story.

However, one game has truly deserved the 'cinematic' label, and completely redefined what it means in the context of the industry. Thirty Flights of Loving is a short, experimental game from indie developer Brendon Chung, released back in 2012. It only lasts around 15 minutes, but it was entirely unlike anything released before it.

It's a game that really uses the language of cinema, in particular editing techniques such as jump and smash cuts, to craft a completely new type of experience. Jumping merrily through virtual space and time, it's cine-literate in the best possible way (and full of references to cult directors like Wong Kar Wai). It remains a vivid, utterly unique experience that anybody interested in interactive storytelling should play.

Chung's game was very much an inspiration for Jonathan Burroughs and Terry Kenny, the co-directors of Virginia and co-founders of the young Variable State studio. In fact, it gets a special mention in the new game's credits.

Virginia indeed shares some methods in common with Thirty Flights... - the use of filmic scene transitions and the lack of dialogue, most strikingly. But Virginia is very much its own beast too.

"Unashamedly cinematic"

Speaking to Newstalk, Terry explained that the word is indeed "bandied around a lot... [But] myself and Jonathan were very open to the idea of making something unashamedly cinematic.”

As soon as you boot up the game, the developers' unapologetic embrace of film language is apparent. The game is presented in a fetching 2.35:1 widescreen ratio, while a message encourages the game to be played at 30 frames per second - it's the lowest 'standard' frame rate for games, but much closer to the rate of 24 FPS, the standard for cinema.

Such moves are relatively 'controversial' in the gaming sphere, with many players demanding smoother, more responsive frame rates and support for all manner of display resolutions.

As for the widescreen display, Jonathan pointed out that cinema uses widescreen "for a reason".

Indeed, when playing the game, the benefits are clear. Previous examples of widescreen games - such as the horror title The Evil Within or the 'cinematic' action game The Order 1886 - have been criticised for the restrictive and sometimes frustrating viewpoint they afford the player, especially when aiming weapons.

Virginia, though, uses widescreen beautifully (it helps, of course, that there's nothing to shoot). Since the game edits to new scenes regularly and unexpectedly, this allows the developers to very carefully 'compose' individual scenes and sights.

Players are given the chance to move around these environments and discover their own compositions, but Variable State also has quite a lot of control over what the player sees, and when. It also allows them to skip the 'boring' bits; why force the player to walk down a corridor when you can simply cut to the next scene? Many games use huge spaces very effectively, but there's something very refreshing about a game that takes a different approach.

"A concise, neat story"

While cinematic in nature and extremely light on gameplay mechanics, Virginia does very much play with the idea of player control and perspective. In one particularly powerful sequence near the end of the game, the developers play with the idea of a 'first person perspective' in quite a poignant and vivid way that simply would not be possible in any other medium.

It's all held together by a beautiful original score, composed by Lyndon Holland and recorded by the Prague Philharmonic Orchestra. It, again, is immensely cinematic in a way games rarely are, enhancing and influencing the pace, mood and emotions of the game throughout.

The embrace of bold visuals, an impressive soundtrack and the film-influenced editing also have a major impact on the game's storytelling.

"A lot of games extend the playtime as much as possible," Terry explained. "But we wanted to tell a concise, neat story." Indeed, this is very much a 'feature-length' tale, taking around two hours to play through altogether. It's the latest in an increasingly long line of games to break away from the 'epic' (and often tedious) length of most mainstream games.

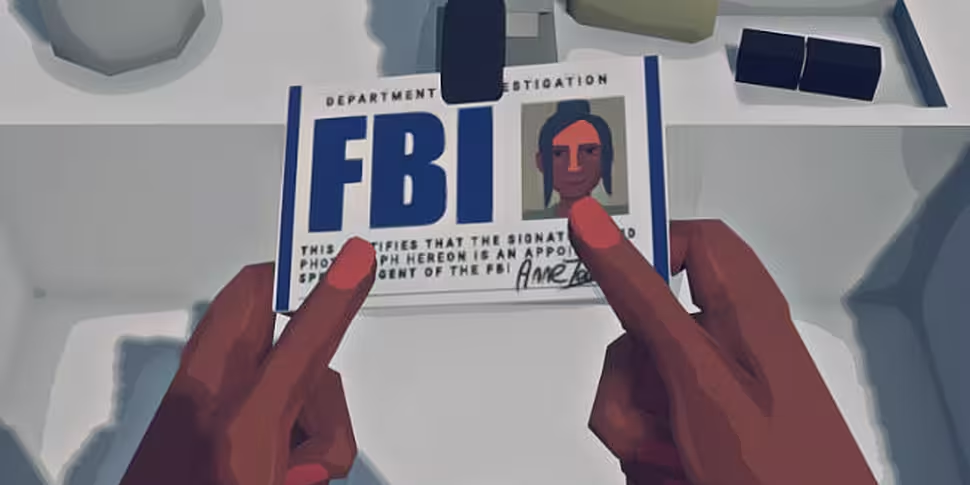

On one hand, Virginia tells a familiar detective story. A recently graduated FBI agent (with a secret ulterior motive) and her new partner (initially cold and hostile) travel to a small town to investigate the disappearance of a young boy. But Variable State conjure up a fascinating dreamlike logic too, where the realms between fantasy and reality are often blurred. It's also full of ambiguities and mysteries. "Through omission, editing is a powerful tool," Jonathan observed.

This approach also helped influence how the game was made, during the testing process and right up until this week's launch. "The thing it allowed us to do [was] more like a film - we were kind of editing and changing things right up until the end of production," Jonathan recalled, contrasting it to more systems heavy games where a minor change or interaction could result in a "Rube Goldberg" like stream of new problems.

Virginia was made remotely, with Jonathan and Terry based in different countries. The rest of the team was also scattered. "Although we're all spread around [...] we all feel like a team," Jonathan said. "It made it very easy to bring other people in." The game was made in the popular Unity engine, while the team also used tools like Skype and Slack to collaborate easily during production.

"It worked out really well. There's tonnes of great tools out there," Terry added. "It's kind of hard to remember what that adjustment period was like, but it was pretty short. The one danger of working locally is that you've always got your laptop there and there's the temptation to check in. You have to make a bit of effort [to not] do that."

Both directors had nothing but praise for their collaborators. In fact, the game's menu includes a special letter to highlight the work of the rest of their team. "There's been so much crossover and bleed between the roles that it was wrong not to call it out," Jonathan explained.

Dublin development

Terry also spoke about the burgeoning development scene in Dublin, where developers like bitSmith and Snozbot are working on their own ambitious titles. While family life and making Virginia left him with little free time over the last year, Terry observed: "When I moved back to Ireland, I made a real effort to get involved. The last [developers' gathering] I went to was fantastic. There was a whole load of people sharing their experiences."

"At that point it seemed like there was so much going on, and beyond people trying to make the next Candy Crush or Minecraft. It was folks with real artistic ambition. I worry sometimes that when people talk about video games, they want to talk solely in terms of making a commercial product. Which is fine, I'm not saying it's a bad thing. But it was fantastic to see others working on different sort of things," he added.

Virginia launched on PC, Xbox One and Playstation 4 earlier this week. While a handful of critics have given it more mixed reviews, for the most part the game has received a very warm and positive reception. In a particularly enthusiastic review, Eurogamer's Christian Donlan gushed: "Virginia is a marvel crammed into a neat two-hour running time, and you must play it."

Terry observed: "When you release [big] games that you work on, you're kind of sheltered from both the praise and criticism because you're just an anonymous part of that project. With a piece of work that's very personal, you feel everything a little bit more."

For Variable State, there'll be some brief downtime before they get back to work on their next game, currently only being teased as 'Project 2'. But with Virginia they have made an immensely assured debut game, and one that truly is 'cinematic' in the best possible way.